On a bright, blustery, afternoon in January 1982, after his team had completed its shoot-around practice in Brown’s creaky old Marvel Gym, Penn basketball coach Bob Weinhauer trudged up to the second-floor offices and extended a hand and an ironic smile to his old buddy, Mike Cingiser ’62, the forty-one-year-old rookie Brown coach.

The two men had first met back in 1965 on Long Island. Over the years, both had become successful high school coaches with big dreams. They’d even lobbied for each other as they landed their jobs at Penn and Brown. Now, on January 8, Bob Weinhauer arrived at Marvel Gym with a tall, athletic team that had won eleven straight Ivy League games the year before and seemed destined for greatness this year, too. And Weinhauer felt terrible about having to put his buddy Mike through what was in store for him that night. But a win was a win, and Weinhauer would take it, even though it would come at Mike’s expense.

For as Weinhauer well knew, Cingiser was something of a legend on Providence’s East Side. A multi-talented athlete in high school, Cingiser had been a star at West Hempstead High School on Long Island, where he led his team to the Nassau County Championship and was named South Shore player of the year. Recruited by schools all over the country, Cingiser chose to attend Brown. For three years he lit up Marvel Gym in a way no one ever had, scoring 1,331 points (then a school record) and earning First Team All-Ivy League honors in 1960, 1961, and 1962. He was drafted in the seventh round by the Boston Celtics, but refused the offer on the advice of Dean of the College Charles Watts ’47, who informed him that Brown was “not in the business of producing professional athletes.” Instead Cingiser chose to stick around Providence, do some graduate work at Brown, and coach the freshman basketball team.

Those who saw him coach that 1963 team might have thought he should have chosen some other line of work. He was a great clinician whose practices were spiced with a little humor, an occasional strained reference to some work of literature, and a hell of a lot of running and shooting. And his record of 17 wins and only 3 losses was remarkable. But he was a maniac. As a player, he had always been a ferocious competitor. Once, after a one-point loss to Penn—the team’s third straight by either one or two points—he had gone to the locker room and put his fist through the glass door. Now, with his old uniform number, 53, locked up and awaiting retirement in Brown’s Athletic Hall of Fame, all his energy was pent up. When a referee made a bad call, or when Cingiser’s emotions were running high, he no longer could find an outlet by committing an offensive foul or hitting an oh-so-satisfying jumper in the face of the opponent. Now he was on the sidelines, in a frumpy jacket and tie. So when the fury built up, as it did often during that 1963 season, Mike Cingiser ranted and raved and cursed his way up and down the sideline. Statistics were never kept for that sort of thing, but he may well have set a single-season record for most referees damned to hell.

In the years that followed, Cingiser calmed down (a little) and returned to Long Island, where throughout the 1960s and 1970s he settled into a nice life as an English teacher and coach, winning 67 percent of his games at Lynbrook High School and twice taking his teams to the county championship game. Then in April 1981 the prodigal son returned home, and after only eighteen winning seasons in eighty years of Brown basketball history, the hope was that things were about to change for Brown.

After three straight winning seasons in 1973, 1974, and 1975, the team had gone 7–19 in 1976, 6–20 in 1977, 4–22 in 1978, and 8–18 the year after that. Not even the 1978 hiring of Joe Mullaney, a successful coach at Providence College and with the Los Angeles Lakers, could turn things around. Mullaney presided over three more losing seasons with his traditional x’s and o’s style of play, and then suddenly left in 1981 when his old job at Providence College opened up again. His players learned of his defection on the evening news. His replacement was Mike Cingiser.

Because he had been hired so late the previous school year, Cingiser had no chance to recruit new players. He would basically need to enter the 1981–82 season with the team he’d inherited. He would train his players hard, very hard, preparing them to play with poise and intensity against larger and more skilled opponents. He would emphasize fundamentals. And he would employ a run-and-gun offensive style, unusual in an era with no shot clock and no three-point line.

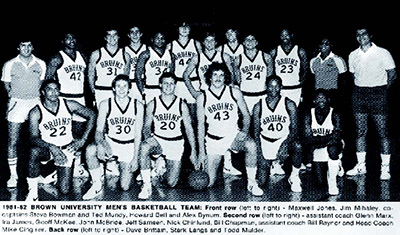

Cingiser brought the team together at Sayles Gym for an organizational meeting on September 22. He looked over his players. Among them were Bill Chapman ’83 and John “Bake” McBride ’84, two defensive-minded forwards out of New York who probably should have been playing guard; Jeff Samsen ’84, a long-range bomber who never saw a shot he didn’t like; Ira James ’83, the team’s volatile undersized power forward and top scorer; Ted Mundy ’82, the tallest starter on the team at six feet, seven inches; Alex Bynum ’84, an energetic but unproven point guard who stood just five feet, seven inches; and Steve Bowman ’82, a reserve shooting guard who had set scoring records while in high school in Western Massachusetts but who had started only one game the prior year, averaged 1.7 points, and shot only 33 percent from the field.

After the players had introduced themselves, Cingiser spoke briefly about his philosophy: up-tempo, fast-breaking, man-to-man defense. He talked fast and excitedly, and when he was done he asked if there were any questions. For a moment, everybody was silent.

“What do you want us to call you?” Ira James asked. “Mr. Cingiser? Mike? Coach?”

“I don’t care what you call me,” Cingiser answered. “It’s how you call me that matters. You can call me son of a bitch, and if you smile, that would be fine.”

The bulk of the team’s practice that season was devoted to learning some sort of choreographed play—an out-of-bounds play, for example, a bounced inbounds pass to the low post man, or a double screen to get someone open on the wing. The players practiced them over and over again. Dressed in corduroy pants and penny loafers, Cingiser would go out on the court and walk the players through it all, demonstrating in slow motion how to pivot your foot and swivel in the lane to face the basket, or how to throw the ball from “box to box,” from one side of the lane to the other. Some players caught on quickly; others didn’t. It was part clinic, part classroom, part comedy, part tragedy.

Through it all, Cingiser was a master. Every now and then he would stick two fingers in his mouth and let out a deafening whistle, as his eagle eye spotted a hole in the defense or a not-fully-extended elbow. He taught, he demonstrated, he cajoled, he whispered words of encouragement. He had his ear on almost every conversation in the gym. He was a coach again, and this gymnasium was his home. He was loving it.

The Mike Cingiser Era began in earnest on the Saturday after Thanksgiving with an afternoon game at Marvel against Stonehill College. The Chieftains, a Division II team, should have been easy prey. Brown had beaten them by eleven points a year earlier, and physically they were even smaller than the diminutive Bruins. But Stonehill scored the first basket and never looked back, running off to a 16–5 lead and racking up fifty-six points by halftime. They hit 68 percent of their shots, and in the end they won by eleven points. When the buzzer sounded, the Stonehill players mobbed each other, elated at having beaten a Division I team to open their season. The Brown players shook their heads in disbelief, and even Cingiser admitted to being a little bit shaken.

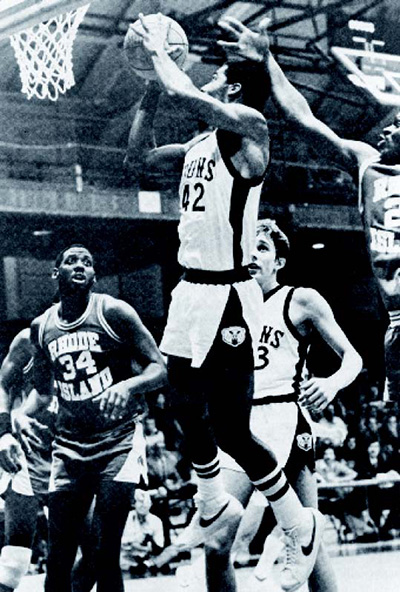

Four days later a tall and talented Rhode Island team came to Marvel and, despite thirty-five points from Ira James, escaped with its thirteenth straight win against Brown, 95–89. Three days after that, the Bruins dropped to 0–3 after a tense four-point loss to Yale.

Cingiser, ever the optimist, was undaunted. He had not expected instant success. He knew that a lack of height and depth were going to be problems all season long. Still, he had seen hopeful signs in the team’s play, particularly its ability to run up and down the floor. But then Brown played poorly in a loss at Hofstra, committing twenty-nine fouls and embarrassing Cingiser in front of his old Long Island coaching friends. The Bears dropped an emotional, high-scoring game at Boston College (after surviving a mid-highway blowout of the bus’s right front tire), and then were trounced by Joe Mullaney’s Providence College, dropping the season record to 0-6. When some reporter noted that the school record for most consecutive losses was twelve—an ignominious mark set by the 1977–78 squad that finished 4–22—the remark made the rounds in the locker room. The team’s mood was turning nasty.

Next came a trip through the South, starting with a shellacking at the hands of the South Carolina Gamecocks, 105–77. Frustration was setting in. Cingiser’s squad would often play one competitive half of basketball, but at some critical point in the second half, a seam would rip open—the foul shooting or the ballhandling or the defense—and Brown would find a way to lose.

The day after the South Carolina game, Cingiser called everybody together in his hotel room for a team meeting. South Carolina, he said, was dead and buried. Hofstra was gone. Stonehill was ancient history. “Matter of fact,” he said, “there are only seven games on the schedule this year that we can’t win. Those are the seven we have already played.” He paced back and forth. “Look, guys, it’s going to end sooner or later. I know we’re there.”

Cingiser pointed out that for the most part the offense had been solid. James was averaging more than twenty points a game, Samsen 13.5, and Bynum more than eleven. Even the defense was starting to come around, the coach continued, and if they could find a way to play with both poise and intensity at the same time, they were going to set themselves up nicely for the Ivy season.

Before their trip was over, though, Brown lost to Florida Southern, the defending Division II national champs; they were outplayed by Georgia Southern; and they lost a 106–96 shootout at Memphis State. Their record now stood at 0–10.

It is often said that adversity brings people closer together, but in this case there was so much togetherness that adversity only made things worse. The players had been together for more than two months now, practicing together, hanging out in the locker room together, studying together, showering together, eating together, traveling together, rooming together. School was hard enough. Here they were devoting all their free time to basketball and they had nothing to show for it. What were they supposed to tell their families? How were they supposed to face their friends?

Cingiser wasn’t ready to give up, however. Next up was the University of New Hampshire, a team he had scouted twice and, as a result, believed was beatable. But on January 6, New Hampshire came into Marvel Gym and ran Brown off the court, 86–71, a huge disappointment that left the players disconsolate. The Bruins were now 0–11, one game shy of the all-time school record for most consecutive losses. Nothing was working. And the next two opponents were perennial Ivy League powers Penn and Princeton, who between them had won the last thirteen consecutive League titles. It appeared that a new school record for consecutive losses was inevitable.

After the New Hampshire game, Cingiser kicked around the court for a couple of minutes and then retreated to his office on the second floor. There he found his daughters, Karen and Lisa, crying hysterically. They, too, had been expecting a win. They, too, had gotten their hopes up, only to have them trounced. And now they knew that this whole move—the interviews last April and the Brown job and the house in Barrington—it had all been a big mistake. The team was going to finish 0–26, and he was going to get fired, and life was going to be miserable.

“Whoa, give me a time-out here,” Cingiser said as his daughters looked up and began crying louder at the sight of him. “I don’t want that from you. I’m not crying, so you can’t be crying. It’s not that bad. If we get fired, we get fired. If we never win a game, we never win a game. But it’s just not worth so much that it can be allowed to haunt you.”

That night, though, when he lay down in bed, Cingiser began to wonder whether he really was capable of coaching on this level. Maybe there was a bigger difference between high school coaching and college coaching than he had thought? Maybe he couldn’t just come in and run the race his way when he didn’t have the horses. If the team did go 0–26, how in the hell would he be able to recruit anyone? Who would want to play for that sort of coach?

In the early 1980s, Brown was still on the old academic calendar, in which students returned from a short December break to a reading period and final exams in January. And so it was that when the ball was tipped to begin the game against Bob Weinhauer’s Penn team on January 8, the small crowd at Marvel Gym included an unusually large number of students seeking some Friday night release from their intensive academics.

The game began as so many had before. Brown jumped off to a quick lead and was up 2–0, then 4–0, then 6–0. But the Quakers, taller, stronger, and better, worked the ball to their big men, who scored eight straight points. Penn began to pull away and soon led, 17–10.

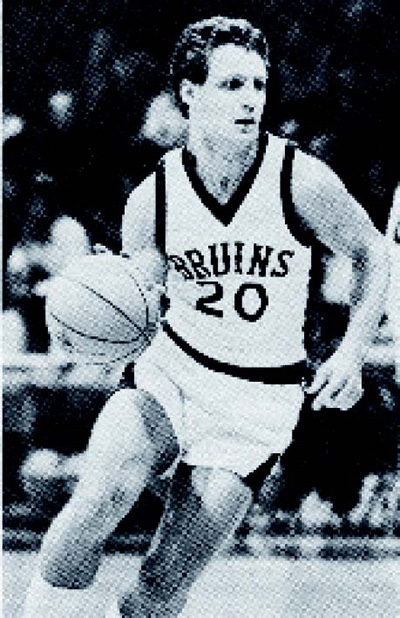

At 12:37, Cingiser called a time-out to try to shift the momentum. His team trailed, 17–10, but Penn soon opened the lead to twelve. The familiar script began to play itself out. Still, the Bruins showed some signs of life, mostly from senior guard Steve Bowman, who had been inserted into the starting lineup and responded by sinking five long jump shots in eight tries, nearly matching his all-time game high of thirteen points. Brown ended the half with a little 10–4 spurt to close to within six points, 38–32.

Penn scored first in the second half, opening their lead to 40–32. Cingiser banged his fist on the scorers’ table. But then Ira James scored three when he was fouled on a shot that bounced around the rim and went in. Then Chapman stole the ball. Bowman hit another long jumper. Another steal by Chapman, followed by a full-court drive for a layup. Brown had scored seven points in a row to cut the Penn lead to one point. The crowd was becoming raucous.

A Penn basket. A Brown basket. A Penn basket. A Brown basket. Two Penn baskets. Two Brown baskets. Penn kept threatening to pull away, but just at that moment one of its players would miss a shot, or Bill Chapman would grab a key offensive rebound, or Steve Bowman would let fly with another twenty-five-footer. The game stayed uncomfortably close. The temperature in the gym began to rise perceptibly. Slowly, the fans started thinking the unthinkable.

With nine and a half minutes left to play, Penn led by two, 59–57. There was a wild sequence of missed shots and loose balls that ended with an offensive rebound and basket by Chapman, who was fouled on the play. Everyone on the bench leaped up and yelled. The fans were stamping their feet. Mundy, James, Bynum, and Bowman engulfed Chapman, who then calmly stepped to the line and sank a free throw. Brown 60, Penn 59.

The fans started chanting, “DE-fense, DE-fense.” It was the amazing sound of confidence and excitement. This was old Marvel Gym, this was oh-and-eleven Brown Freaking University! The lead seesawed back and forth. The Penn band beat on its bass drum, two quick hits followed by a pause, repeated again and again, like a clock ticking down.

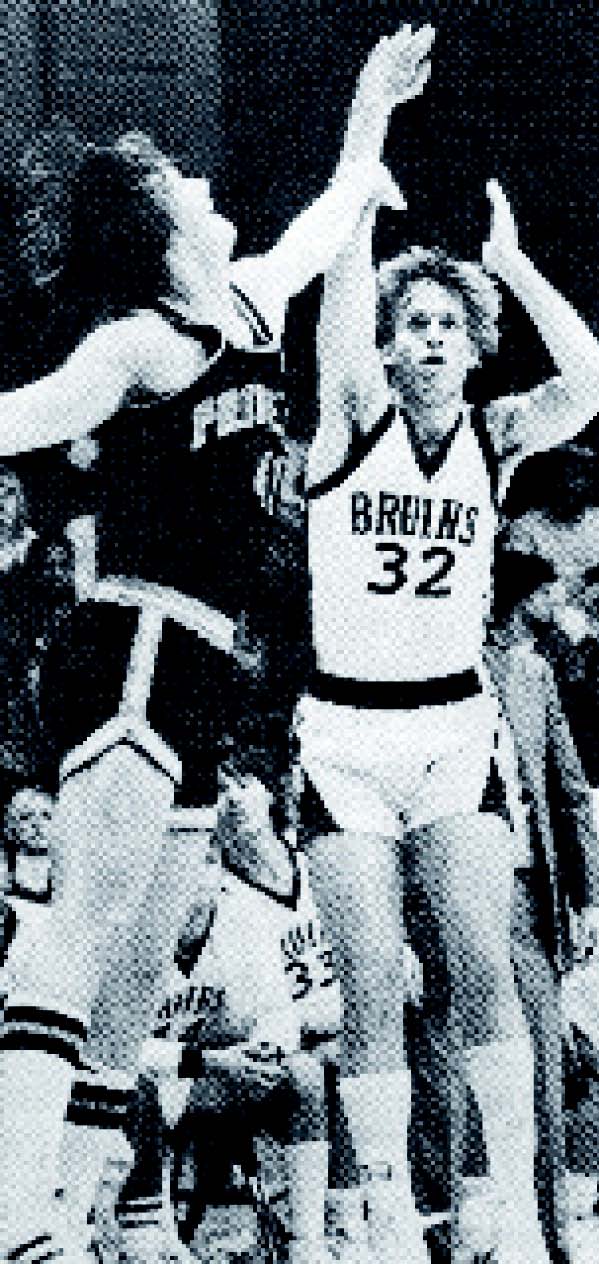

With nineteen seconds left, Brown was ahead by one point, 74–73. The fans were on their feet, yelling into the rafters of the ancient gymnasium. Penn then turned the ball over and fouled James. As he stepped to the free throw line, the gym became so quiet you could hear a losing streak snap. Swish (roar!). Swish (roar!). Brown 76, Penn 73. The Quakers scored a meaningless basket, and then it was over.

The players grimaced with emotion and surrounded Bowman, the unexpected hero. Coach Weinhauer, meanwhile, approached Cingiser with an extended hand. “I hate you,” he said to his old friend, laughing as the crowd kept cheering. “How did you do this?”

Brown was now 1–11.

The celebration went on for a blissfully long time that night. It was probably the sweetest moment Marvel Gym had ever known, or could ever hope to know.

The next night the miracle continued against Princeton. Bowman, the erstwhile reserve, continued to have a hot hand. He sank six of seven shots in the second half, scored a career-high twenty points, enough to be named Sports Illustrated’s Player of the Week. Final score: Brown 58, Princeton 53. The Bruins had knocked off the League’s two perennial powers on consecutive nights. Providence-Journal reporter Jim Donaldson wrote, “It was a turnaround as shocking as if Ted Kennedy had announced he was joining the Moral Majority.”

It hardly mattered that the team would finish the season a miserable 5–21. Nor that Penn would go on to win the Ivy League. Nor that no Brown player in uniform that night would ever enjoy so much as a winning season, let alone be there to enjoy the supreme achievement four years later, when Cingiser would lead Brown to its first, and still only, Ivy League title. Over the course of one weekend, suffering had given way to euphoria. Memories had been minted. Faith had been restored.

Joe Dobrow served as statistician, public-address announcer, and chronicler through seventy-one losses and too few wins from 1981 through 1985. He claims to be one of four basketball fans to storm the court at Dartmouth when Brown clinched its 1986 title. He can be reached at [email protected].