When, during the turmoil of the late 1960s, the University needed someone to lead the Afro-American Studies program that students demanded be added to the curriculum, it searched for someone who could be a scholar, a leader, and a visionary all at once. Officials found their man in Europe: Charles H. Nichols, who’d earned his doctorate from Brown decades earlier. Nichols, a professor emeritus of English, died in Providence on January 18, after a long illness.

When he was recruited to head the Afro-American Studies program, Nichols was directing the American Studies department at the Free University of Berlin. He had earlier been a Fulbright professor at Aarhus University in Denmark and had taught at Hampton University in Virginia. One of his students, Harvard African American Studies professor Werner Sollors, remembers that Nichols “taught American literature in a utopian, integrated fashion,” mixing Langston Hughes and Sterling A. Brown with T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, Melville’s “Benito Cereno” with Twain’s The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson. Many scholars were—and continue to be—familiar with one side of this equation, but few with both.

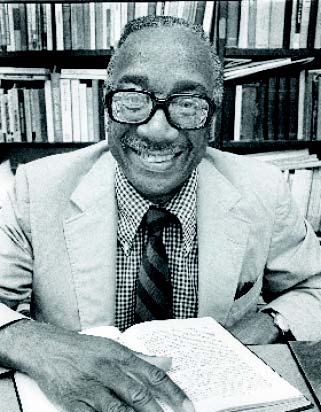

Nichols arrived at Brown in July 1969 and was notable for his stylish boots and three-piece suit, and for eyebrows that lifted up when a point was to be emphasized. Formal in appearance, he was nevertheless warm in nature. Momentum had no better ally. He looked around, wondered, planned. Where was the connection between town and gown? he wondered. He said, “We will establish a community-relations seminar to bring local black leaders to the campus each week for lectures and discussion.” He went to Manhattan to recruit George H. Bass, executor of the Langston Hughes estate, telling him, “The students need help. You will develop an historic research theater and performing arts component.” It was called Rites & Reason, and it too stretched out its arms, inviting all to connect with its vibrant dramas.

Within a dozen years Brown’s Afro-American Studies program was ranked fourth in the number of articles published in scholarly black studies journals and fifth in the number of faculty on the editorial boards of these journals. Brown’s pioneering interdepartmental concentration, founded by Nichols, was soon ranked in the top fifteen in the country by the Chicago Center for Afro-American Studies.

Nichols taught, counseled, charmed, and encouraged several decades of students. He advised dissertation writers on William Carlos Williams, Henry James, Walt Whitman, Duke Ellington, Japanese American literature, John A. Williams, and Melvin Tolson. He produced his own scholarly works, starting with the laudable Many Thousands Gone, which had grown out of his dissertation about the slave narratives. He edited the Arna Bontemps–Langston Hughes Letters and published monographs on Sterling Brown and others. His drive propelled him beyond campus to accept not only awards from associations and conventions, but also to accept invitations to lecture at universities here and there.

In 1993, the modest professor accepted the Charles H. Nichols Award, given to the Rhode Island resident who contributed the most to the scholarly knowledge of black people. By then the agents who had identified him knew better than to offer more than congratulations. They had learned that if you were indelicate enough to compliment “Nicky,” as Millie, his wife of fifty-six years called him, his eyebrows would go northward and he would say, waving a hand, “Oh…stop it.”

— Barry Beckham ’66

Barry Beckham is an author in Washington, D.C. He is a former Brown professor and a close friend and former student of Charles Nichols, who hired him in 1970 “part-time for a year” then kept him at the University for seventeen.