In 1995, Jim Yong Kim started a community health center in Carabayllo, Peru, a slum on the outskirts of Lima. For several years he’d been helping his friend Paul Farmer run Partners In Health, a Boston-based nonprofit they’d founded to support a free clinic in Haiti’s destitute central plateau. Realizing that medications alone could not cure the sick in places as poor as Haiti, Farmer and Kim gave patients such basic necessities as clean water with which to take their pills, food to stave off malnutrition, and tin roofs to replace the leaky thatch that allowed rain to seep through.

To reach those who were too feeble to travel to the clinics, the doctors trained community health workers to visit their homes. By 1995, Partners In Health had treated tens of thousands of patients, many of them infected with HIV, tuberculosis, or a deadly combination of the two.

In Peru Kim planned to build on that success and expand its reach. His goal was to create a model for health care in poor countries worldwide. He chose Carabayllo at the urging of a friend, a Catholic priest who’d supported Partners In Health in Boston and was now living in Lima’s shantytowns. Then the priest died of tuberculosis, and it became clear that Kim and his colleagues were facing a much larger project than they’d anticipated.

Cultures revealed the disease that killed Kim’s friend to be resistant to all five of the main drugs used to fight tuberculosis. More frightening still, the Lima health center found another ten cases of what looked like drug-resistant tuberculosis in the surrounding area.

Treating drug-resistant tuberculosis is a complicated proposition, as Kim and Farmer knew well from their experience in Haiti: a course of at least five drugs must be administered for up to two years, and in those days the cost was more than $20,000 a patient. While drug-resistant tuberculosis was not uncommon—more than 500,000 people become ill with it annually—most of the disease’s victims are impoverished, and there was little price competition for their business. Furthermore, the World Health Organization’s official stance in the 1990s was that, in a world of finite funding, treating drug-resistant tuberculosis in resource-poor nations was simply not an efficient expenditure. It would draw attention and money from treating forms of the disease that did respond to the usual drugs.

Even the government of Peru resisted treating the outbreak in Carabayllo. The country had implemented a rigorous tuberculosis treatment plan endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and was being hailed as a model for control of tuberculosis in the developing world. Health officials didn’t want to hear anything that might undermine that program—especially not from a pair of idealistic North American doctors.

But letting poor people die because treating them was not cost-effective went against everything Kim valued. Born in Seoul, South Korea, he’d grown up in Muscatine, Iowa, population 22,000, listening to his theologian mother engage her children in nightly political and ethical discussions. A student of Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Kim’s mother had encouraged him as a boy to read the writings of Martin Luther King Jr. She’d taken him to hear George McGovern speak and to volunteer for the candidate when he ran for president in 1972. “At twelve I was campaigning for McGovern,” Kim says, “me and like three other people in Iowa.”

His mother’s influence stuck. Deeply committed to social justice and liberation theology, he’d devoted his medical career to caring for the poor. Now, in Peru, “we were watching entire families infect each other and die,” he says. The challenge was to cure those patients without angering the international health community. In the process of meeting that goal, Kim and Farmer catalyzed one of the most effective global health interventions in recent history.

From the start, Jim Kim’s career has been intertwined with that of Paul Farmer, whom he met in 1988. Farmer, the subject of Tracy Kidder’s best-seller Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, a Man Who Would Cure the World, had been working in Haiti for four years and had incorporated Partners In Health just months before they met. Kim swiftly signed on as a cofounder. Together, the two completed their MDs and PhDs in medical anthropology, applied to residency programs, and joined the Harvard Medical School faculty, running Partners In Health on the side. Bit by bit the project in Haiti grew, hiring medical staff, training outreach workers, and building a hospital and additional clinics.

That year Kim won a Leadership Fellowship from the Kellogg Foundation, which “got me thinking about leadership, about what it would take to create a global movement to change the health prospects for poor people,” he says. With his grant money, he decided to try and lead that change by building a model health center. “I said, ‘Paul, we can start a global movement.’ And he really did say, ‘Let’s start with ten patients.’ ” Tracy Kidder recounts that conversation in Mountains Beyond Mountains, and it sounds apocryphal. But Kim swears it happened just like that.

They called the Lima program Socios En Salud. By that time Farmer and Kim were familiar with treating not only AIDS and tuberculosis among the poor but also drug-resistant tuberculosis, which usually develops in patients who stop taking their medications too soon. They stop because they may have started to feel better, or they may have been unable to afford continuous treatment. They may have received diluted black-market drugs. To prevent these conditions from arising, WHO promotes a program called DOTS (directly observed therapy short-term), in which patients receive every dose of medication directly from a health care worker. But the patients in Lima didn’t fit this norm:some had never been treated for tuberculosis; others had clearly complied with DOTS treatment and received carefully monitored medication. These patients seemed literally to have caught a resistant strain from thin air.

Initially Kim and Farmer simply treated the Peruvian patients themselves. They bought the more expensive drugs on credit at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the Harvard teaching facility where they worked. But at $20,000 a pop, that was not a viable solution. To solve the larger cost problem, Kim fell back on his dissertation research on pharmaceutical pricing and led a global effort to drive down the cost of the drugs. First he convinced WHO to add them to its list of essential medicines. That created a potential market, and with new competition from generic drug manufacturers, the cost of the medications dropped 90 percent.

In 1999, when the first group of Socios patients had achieved an 85 percent cure rate, WHO reconsidered its approach. The agency’s leaders created a new program for drug-resistant tuberculosis called DOTS-Plus, put it under strict WHO control, and made Kim chairman. Saving the lives of people with drug-resistant tuberculosis had become cost-efficient.

In 2000 the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation gave Partners In Health $44.7 million to broaden the program throughout Peru, establish a model, and export it to Russia, where drug-resistant tuberculosis is widespread. “It was a huge grant at the time,” recalls Kim. “It changed the thermostat for global health.” Since then, the program has been replicated in more than thirty countries, where it has treated some 30,000 cases of drug-resistant tuberculosis. The economist Jeffrey Sachs, Kim says, told him and Farmer it was time to stop asking for millions and start asking for billions. For his efforts, Kim received a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 2003. (Farmer had been awarded one a decade earlier.) In 2005 U.S. News & World Report included Kim and Farmer in its list of America’s Best Leaders. Last April, Time named Kim one of the 100 most influential people in the world.

Kim was not the first pioneer in his family. His great-grandfather was among the early Korean converts to Christianity. (He converted while living in China.) In addition to Kim’s mother, two of his uncles were also theologians. His was oneof only two Asian American families living in Muscatine while he was growing up. “I think the other family ran the Chinese restaurant,” he says. In the mall, kids would come up to him and make fake karate moves, yelling “Ay-aah!” On the basketball court, he says, kids spit on him.

When he got his ACT scores back, Kim recalls, his guidance counselor was elated: “Wow, with scores like these, you could go to Iowa. Maybe even Minnesota or Wisconsin if you wanted.” Kim won an engineering scholarship to the University of Iowa, but the summer before he got there, he attended a science program “with lots of Jewish kids from New York,” he says. “I felt like I had met my kindred spirits.” His new friends persuaded him he’d be happier at an Ivy League school, and even before setting foot on the Iowa campus he’d decided to transfer, applying to Harvard and Brown. Harvard turned him down, so Brown it was. “My father cried when I came east,” he says. His mother and sister, Heidi, drove with him, and Heidi ’85 followed her brother to Brown three years later.

Kim arrived in Providence in 1980, when identity politics was an increasingly hot topic on campus, he says: “There were still Asian American kids at Brown who were embarrassed by their backgrounds.” Thrilled to find a place to talk about race and ethnicity, he spent much of his free time in the Third World Center, “hanging Black” and developing an ear for Black English. On Parents Weekend, he and his friends would march around campus protesting and scaring parents. “It was just the most fun thing we could think of,” he says, grinning widely and laughing at his younger self.

He and his friends stayed up late into the night debating the strategies of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. But when Kim told his father, who was a dentist, that he wanted to study philosophy, the response was clear: “You can do whatever you want—after you finish your residency.” You’re Asian, his father warned him, and in a white country you need a skill. So Kim concentrated in human biology and went to Harvard Medical School, where he added a doctoral program in anthropology. With a fellowship to study in Korea, he learned the language and traveled to his homeland expecting to sharpen his identity there. But in the end, he says, “it fell flat for me.”

When Kim met Paul Farmer during their second year of med school, he found his perfect counterpart. They shared the same idealism and the same goofy college-boy sense of humor. They had the same kind of late-night discussions Kim had loved at Brown. But instead of identity politics, Kim and Farmer talked about liberation theology, which seeks to emulate Jesus’s “preferential option” for the poor. They talked about the need for moral clarity. “Me and you, Jim,” Farmer prodded him, “what do we want to do with our lives?”

“The people I used to talk identity politics with [at Brown],” Kim says, “many of them are bankers. I’m glad that there are African American presidents of banks. But that’s not my struggle.” With Partners In Health, Kim had found his calling. “We thought we’d start small, with the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere,” Kim recalls.

Kim’s success with Socios propelled him onto the international stage. In Peru, he’d met WHO’s tuberculosis chief, Jong-Wook Lee, a Korean doctor who had married a Japanese nun and had worked on leprosy before switching to tuberculosis. Kim surprised Lee by addressing him in Korean, and the two formed a fast friendship. When Lee decided to run for director general of WHO, he asked Kim to organize his campaign. After Lee won, he told his friend, “Come help me run WHO.” With no idea what lay ahead, Kim persuaded his wife to sell their house and move with their young son to Geneva. Kim had no job title and little idea of the cultural divide that lay ahead. “It was a modern-day Korean American version of the Beverly Hillbillies,” Kim says.

It was impossible to find good Chinese food in Geneva, and even the bad food was expensive—a combination, he jokes, that’s a sure sign of a declining economy. A city regulation made it illegal to flush the toilet after 10 p.m. Kim and his wife flushed.

WHO’s byzantine bureaucracy was the antithesis of Partners In Health’s nimble, freewheeling atmosphere. Kim pushed technology on a culture that still got its news from TV. “I’m the hated guy who introduced Blackberries to WHO,” Kim jokingly told a class of Harvard medical students this fall.

To illustrate the political impediments to change at WHO, Kim described his experience managing a new set of dietary recommendations. He’d proposed that sugars be limited to 10 percent of a child’s diet. First the Cubans spoke up to defend sugarcane. Then the United States, with its large soda industry, voiced its very strong objections to the proposal. Kim says it’s the only time he ever saw Cuba and the United States agree on an issue. Then the Philippines, a coconut producer, began a protracted discourse on the merits of long-chain versus medium-chain fatty acids.

“How do I defend WHO?” Kim asked the students rhetorically. “It’s indefensible.” Still, he argued, WHOhas a role to play. He pointed to the 2003 SARS epidemic in China, which was just easing up when he arrived in Geneva and took over its supervision. “You aren’t too young to remember SARS, are you?” he asked students. Only WHO, he explained, had the authority to set the international travel restrictions needed to contain the outbreak. In the event of an avian flu epidemic, he continued, only WHO has the authority to go into a country and conduct investigations. “This is probably the reason WHO will never be dismantled,” he told his students. “Somebody’s got to be able to go in.”

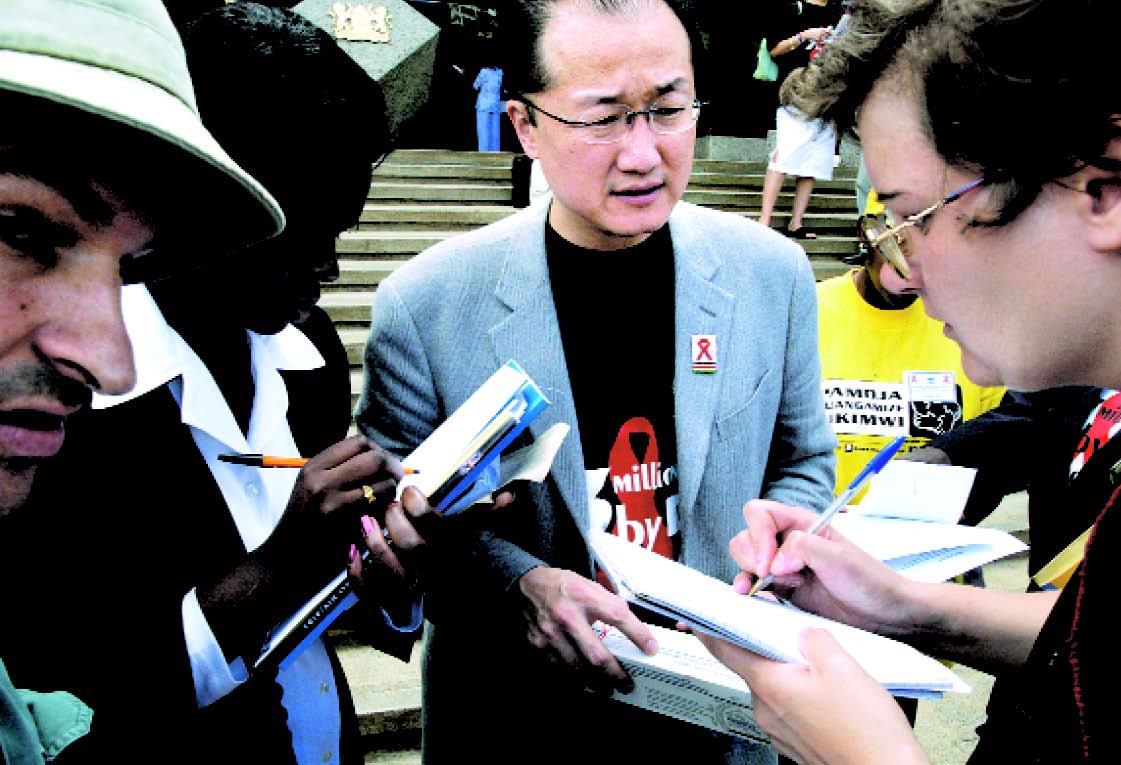

When Kim came to WHO, he served as assistant to the director general. Then in 2004 the chief of the HIV-AIDS program resigned because of bad health, and Lee asked Kim to take over as director of WHO’s most ambitious initiative. The previous year, countering the advice of many at WHO, Kim had encouraged Lee to embark on a global campaign called 3 by 5, which aimed to treat three million new HIV and AIDS patients—half the infected population globally—with antiretroviral drugs by 2005. Kim wound up running the program. Although 3 by 5 failed to meet its target (“We started too late and didn’t move fast enough,” Kim says), it succeeded in getting drugs to more than a million new patients and increased treatment in Africa eightfold. Political pressure and public scrutiny forced even reluctant nations like South Africa to face up to the enormity of the problem. “Where Jim really distinguished himself was in his willingness to set the bar high and not be afraid to tell developing countries what they need to do to contain the epidemic,” says Kenneth Mayer, who directs Brown’s AIDS Program.

But Kim’s outspokenness was not always welcomed. When he announced in 2004 that the 3 by 5 campaign was not going to meet its target and accused South Africa, Nigeria, and India of foot dragging, he infuriated South Africa’s health minister, who held that AIDS is not caused by HIV and who advocated the use of garlic and beetroot to cure AIDS. Kim found himself in a public brawl with not only the health minister but President Thabo Mbeki. To his students, Kim joked that had he gone easier on Mbeki, he might still be working at WHO.

Last May, Jong-Wook Lee died suddenly of a massive subdural hematoma, and Kim and his family returned to Boston. Now Kim is planning the next stage in his career, temporarily working out of a barely furnished office in a neglected looking brownstone that houses Partners In Health. It’s located smack in the middle of the three Harvard divisions in which he holds appointments: the School of Medicine (a professor of medicine, he chairs the Department of Social Medicine), Brigham Women’s Hospital (where he is chief of the Division of Social Medicine and Global Health Inequalities), and the School of Public Health (where he runs the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights). He’s thrilled, he says, to have the sizable endowments of those three institutions behind him and to be free of constant fund-raising.

“For years,” Kim says, “Paul and I thought we’d be rattling our sabers forever, trying to raise $100,000 here and another $100,000 there.” For most of its nearly twenty-year history, Partners In Health was kept afloat by one of its original cofounders, a Boston developer named Thomas J. White, who was determined to give away his riches before he died. White has donated $75 million to Partners In Health and other charities, says Kim; his coffers are now dry.

In 2000 Farmer and Kim saw the beginning of an unprecedented level of help. “The first shot across the bow was GAVI,” says Kim, referring to the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization, the Gates Foundation’s $750 million campaign to vaccinate children worldwide. Over the next few years both governmental and nongovernmental organizations upped and re-upped the ante to fight the biggest killers in developing countries. The G8 nations committed to finance the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. Former President Bill Clinton created his Initiative for HIV and AIDS. In his January 2003 State of the Union Address, President George W. Bush announced the formation of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

The Gates Foundation has stated its intention to develop the tools for preventing HIV infection—vaccines and microbicides that kill the virus. Those are still years away, Kim stresses. Still, existing treatments have made HIV much more treatable in not only wealthy nations but poor countries, too. Once a complicated cocktail of antiretroviral drugs that had to be taken on a strict schedule, so-called triple-therapy for HIV can now be dispensed in a single pill, taken twice a day. The Clinton HIV-AIDS Initiative, headed by Ira Magaziner ’69, negotiated price cuts that have brought down the cost of that treatment to as little as $140 a year.

With millions from the Soros and Gates foundations and Eli Lilly, Partners In Health is helping treat drug-resistant tuberculosis in a Russian prison population that is widely infected with both HIV and tuberculosis. Last year the Clinton HIV-AIDS Initiative funded Partners In Health’s AIDS program in Rwanda, rebuilding a half-demolished hospital and developing a community-based program like those in Haiti and Peru. In Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood, Partners In Health trains local health workers to deliver care to impoverished AIDS patients. Next up are projects in Malawi and the tiny Kingdom of Lesotho, where one in three adults is HIV-positive and a new form of extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis has appeared.

With big donors and foundations willing to take on the huge technical challenges of curing preventable diseases, Kim says medicine needs to take responsibility for making sure it uses that money well. His current Holy Grail is a program in global health implementation and effectiveness that he is creating at Harvard. “We have to get much better at implementation,” he says. “We have to develop a whole new science.” Even in the United States, he argues, “delivery is the gaping hole in the system. We pay attention to delivery in the hospital, but once the patient leaves the hospital …” He shakes his head.

He has raised the first couple of million dollars for the program, and has signed on a handful of faculty including Farmer, Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter, and pediatrician-turned-quality-improvemet guru Don Berwick. Kim’s goal is to identify the most effective medical practices available and to train the next generation of doctors to implement them.

Everything changed, he says, when Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett announced that they would donate billions to cure the poor. “The challenge now,” says Kim, “is to make sure we don’t waste that money.”

Charlotte Bruce Harvey is the BAM’s managing editor.