In 1972 George Gordon was an ambitious, can-do adman working in New York City when he was struck by a bold idea. He would get Alexander Calder, the world-famous sculptor known for his playful, colorful mobiles, to decorate a jet airplane. After all, Calder invented kinetic art, art that moved, and airplanes could be thought of as mobiles without the wires. Besides, if Gordon could get an airline to sign on as the project’s sponsor, he might be able to nab a major new account.

The only problem was convincing Calder.

The American-born artist was living in the Loire Valley region of France. Gordon dialed directory assistance, and the French operator, to his great surprise, patched him through.

“I am Calder, and I am an artist, and this is my home. What’s on your mind?” Calder barked into the phone after Gordon had introduced himself.

“I have an idea for you.”

“What’s the idea?”

Gordon insisted it was too big to describe over the phone, so he suggested a meeting.

“You’re an insistent fellow,” Calder said, but then invited him for lunch. Gordon booked a flight, and a few days later he was breaking bread with one of the greatest sculptors of the twentieth century.

When Gordon showed up for his lunch with Calder, the artist told him to sort his mail. Then he took him on a car ride to one of his studios, driving, Gordon recalls, with his eyes “rarely looking straight ahead. He veered to the right when you talked to him.” After they ate a lunch of soup, pat8E, leg of lamb, homemade bread, and two bottles of 1971 Bordeaux, Calder took a two-hour nap. Finally, after Gordon announced he was going to have to leave soon, Calder said, “What do you want me to do?”

“I want you to paint a plane,” Gordon replied.

“I don’t paint toys.”

“No. I mean a big jet.”

“His face lit up,” Gordon recalls. Calder agreed to paint the jets for $100,000 a pop—his agent felt he should have asked for a million—and Gordon persuaded the now defunct Braniff International Airways to sign on as sponsor.

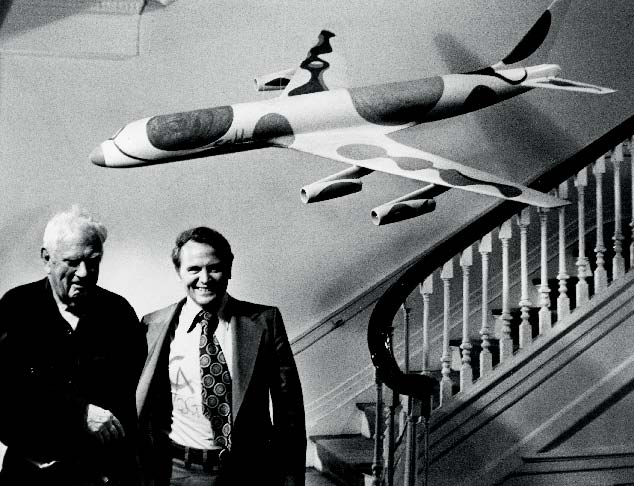

For the next five years Calder and Gordon collaborated closely on two multicolored planes that Calder called “flying mobiles.” Gordon, who at times was jetting to France every week to work with the artist, did everything from dabbing the paint on Caldermodels to getting pleasantly inebriated with the artist over lunch. He also had the good sense to keep detailed notes of his experience and is now writing a book he has tentatively titled Plane Fun.

“We had so much fun,” Gordon, who is now eighty years old, recalls. “The project was a spectacular success.”

The Braniff advertising account also brought Gordon’s firm $25 million and enabled Gordon to start his own ad agency. The first of Calder’s airplanes was christened in 1973 and flew regularly to South America. The second came along in 1976 to commemorate the U.S. bicentennial. Braniff, meanwhile, scored a public-relations coup because of all the media attention the planes received.

Gordon says Calder’s workday consisted of making sketches, then painting the ones he liked onto six-foot-long airplane models. He remembers Calder once drawing a picture of a monkey with “prodigious genitals,” which Gordon politely suggested was probably not the best image to display on the side of an airplane.

What Gordon remembers most about the experience was Calder’s sheer joy at work. “When you hit his funny bone, his laughter would start at his toes and erupt into laughing grunts,” Gordon recalls in Plane Fun. The two laughed together and became friends. “When you were his friend, you were his friend for life,” Gordon says. “He’d do anything for you.”

Calder died in 1976 while completing his third plane for Braniff. By the end of the 1970s, Braniff was in serious financial trouble and no longer wanted to bear the cost of maintaining the artistic masterpieces. Gordon cobbled together a group of investors to buy the planes, but by the time they’d gotten the money together, Braniff had painted them over. “They are probably in some junk heap somewhere,” Gordon says. “It’s tragic. They should be in museums.”

Gordon, who lives up the Hudson River from New York City, still owns a dozen models of the Calder planes as well as twenty sketches. The models, he says, may be worthwhile collector’s items, but that’s not why he keeps them. They are, he says, reminders of an experience that changed him forever. —Lawrence Goodman