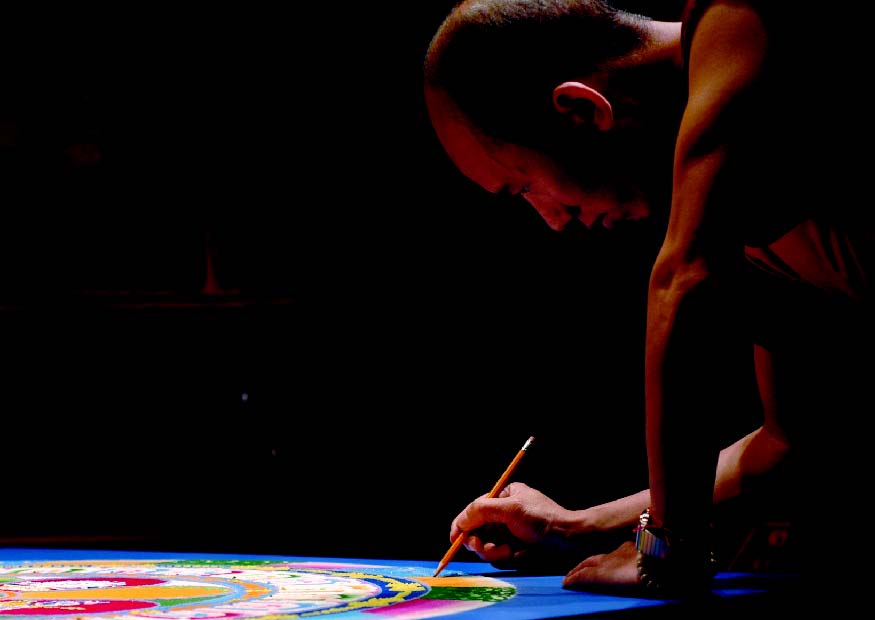

The artists used an unusual medium that encouraged an unusual approach. Tibetan Buddhist monks Tenzin Thutop and Lobsang Gyaltsen, representing the Dalai Lama’s Namgyal Monastery in India (via its satellite branch in Ithaca, New York), were on campus to demon-strate the Tibetan Buddhist ritual art of sand mandalas. For four days they labored painstakingly to create, one grain at a time, an exquisite sand painting that measured four feet in diameter and represented the dwell-ing place of a buddha.

Traditionally, Tibetan Buddhists use sand mandalas as visualization aids for meditation during certain religious ceremonies. According to Kevin P. Smith, deputy director of Brown’s Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, which brought the monks to campus, they have only been displayed outside this ritual context since 1988. The Dalai Lama, he says, allowed the public creation and viewing of mandalas “as a way of reaching out to the world and extending the blessings associated with it.” Namgyal Monastery’s Web site says the Dalai Lama hoped it would help preserve Tibetan culture and bring benefit, “as it would enhance the lives of all living beings near the construction site.”

Traditionally, Tibetan Buddhists use sand mandalas as visualization aids for meditation during certain religious ceremonies. According to Kevin P. Smith, deputy director of Brown’s Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, which brought the monks to campus, they have only been displayed outside this ritual context since 1988. The Dalai Lama, he says, allowed the public creation and viewing of mandalas “as a way of reaching out to the world and extending the blessings associated with it.” Namgyal Monastery’s Web site says the Dalai Lama hoped it would help preserve Tibetan culture and bring benefit, “as it would enhance the lives of all living beings near the construction site.”

The monks’ visit was sponsored by the Barbara Greenwald Memorial Arts Program, whose purpose is to bring non-Western arts to campus and the general public “in a living way.” Earlier events have included Inuit printmaking demonstrations and Laotian classical music and dance. Unlike traditional static exhibits, these “give artists the voice to explain and discuss their role in society and their view of the world,” Smith says.

In this case, the monks “spoke” mostly through their silence. In Haffenreffer’s Manning Hall Gallery off the College Green, they worked under bright lights to the rhythm of recorded Tibetan chanting. They filled cone-shaped tools from a bright palette of sands, arranged by color in plastic cups that bore the Brown seal. Gently rasping one metal cone against another, each monk scattered a few grains at a time, gradually developing a design of intricate pattern and delicate detail. Onlookers stood quietly transfixed.

Keni Sturgeon, the Haffenreffer’s curator of programs and education, remarked that the silence was unusual for museum- goers. “I think it communicates a certain reverence, a sense that something important is happening.”

Many visitors returned day after day. Sturgeon says she was struck that some students brought books with them and stayed for hours. “They’ll watch for ten minutes or so, then they’ll read for awhile, then they’ll watch again and take some pictures, and then they’ll read some more. It is something that doesn’t usually happen in a museum exhibit. Usually people come to look and move on.”

For this program the monks created the mandala of the Buddha of compassion, Chenrezig. The monks began each day with prayers and chanting. As they worked, Thutop said, they tried to generate compassion and reflect on the meaning of the symbols. He said he hoped onlookers would get “an imprint of compassion” through seeing the design, watching them work, and reading the written explanations. “The mandala itself carries some energy,” he added.

After the monks finished the mandala, nearly 200 people watched them ritually dismantle it and sweep the sand into a vase. The monks then led a procession down College Hill to the Providence River and poured the sand into the water, blessing its inhabitants.

Thutop said he didn’t feel a sense of loss when he destroyed a mandala. Buddhism sees everything—including our faith, our views, and our identity—as transitory, he explained: “We shouldn’t cling.” By contrast, Sturgeon says, the Western way “is geared toward permanence and keeping things and collecting things.”

Thutop added that impermanence also has a creative aspect. Since the mandala has a beginning, it also has an end, he said.

And because it has an end, there is a possibility for a new beginning.

—Linda Heuman