Bright Day of Justice

Fifty years ago, on August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, energizing the civil rights movement. Former Brown president Ruth J. Simmons, just eighteen at the time, reflects on the influence of King on her life and thought, as well as on his continuing inspiration for people seeking freedom and equality today.

After graduating from college, I spent the 1967–68 academic year as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Lyon in France. Toward the end of that time, a group of student friends and I decided to go camping in northern Spain. Among these friends was Nicholas, a Catholic priest from the Central African Republic who was studying at the Grand Séminaire de Lyon.

By April of 1968, he had become a close friend and a source of helpful perspectives about African religion and philosophy, politics, and literature. Our planned trip was one of several jaunts I enjoyed with these friends who, when public transportation became immobilized in Lyon during the student riots of that year, also drove me to Geneva to get a flight back home. Though somewhat uneasy about camping that spring, I was happy to be in their company and was actually enjoying our trip—until the morning of April 5, 1968.

Just after dawn on that cold sunny morning, Nicholas entered my tent. Still asleep, I was jolted by a short but loud and insistent phrase that he was repeating. An elegant and forceful speaker, he spat out each word in a way that remains vivid for me many decades later: “Ils l’ont tué! Ils l’ont tué! Ils ont tué Martin Luther King!” Accustomed to the prankster in Nicholas, I initially thought he was exceeding the bounds of good taste with this reference to King’s death, but he soon softened his tone in order to persuade me that the news he brought was true. Others in our group soon confirmed the tragic news. Understanding the significance of this for me, a young African American, my friends quickly gathered up our belongings, broke camp, and hurried into the nearest town to find out more about what was happening in the United States in the wake of King’s assassination.

Many whom I had met in France that year were fascinated with the social and political environment in the United States. Our Fulbright orientation had warned us of the questions that would inevitably be posed about America. After seven months fielding accusations about U.S. domestic and foreign policy, I had become especially familiar with the problem of trying to provide satisfying answers, especially those about the violence and discrimination prevalent in the South, where I was born. What was it like to be black in America? Why did blacks not have the full rights of citizenship? Would I ever choose to leave my country permanently to find freedom elsewhere? I knew that the assassination of King would intensify and expand these questions, and finding answers that they could understand would be even more difficult. I also wondered if I would be able to find good enough answers for myself.

That morning, after a short trip by car, we arrived at a small plaza in the center of a nearby town whose name I can no longer remember but whose vivid images that day remain imprinted on my memory. Townspeople milled about, making purchases or standing near the kiosk where we sought newspapers; they seemed to be in animated conversation about the day’s headlines. The shock and grief of their faces made King’s death even more real. Nicholas’s anger and distress when he broke the news to me had been understandable: the personal and political toll of securing full freedom in post-colonial Africa gave African students a special interest in the struggle of blacks in the United States.

I was startled, though, by the stricken reaction of people who had no particular attachment to Nicholas’s world or mine. Experiencing this historic event in a place so distant from the reality of the American south, I realized for the first time in my life the far-reaching impact of King’s words and actions. In the days that followed, I began to see him in an entirely different light, one that would ultimately lead me to an understanding of how to make my own way in a confusing world.

As we returned to Lyon, I tried to understand and explain what was happening at home: the riots, Robert Kennedy’s impassioned words at King’s funeral. The experience was intensified by the fact I was slowly coming to terms with a pervasive sense of regret that I had failed to recognize King’s importance. Having grown up in a segregated world where racial hatred and violence were commonplace, I was certainly aware of how dangerous it was to challenge that status quo. It had been difficult to fathom how King could believe that his message of love could successfully challenge that reality and all that came with it. Now I realized that, in the face of the ongoing opposition to civil rights, King’s death called upon us to set aside our skepticism to further the ideals and goals that he articulated. I was ready to return home and set a course for whatever role I could play.

Martin Luther King Jr. was much reviled during his life, not only by whites but also by many blacks. His message of nonviolence was embarrassing to some African Americans, many of whom, having experienced monstrous crimes of loss and inhumanity, could not find it in their hearts to believe that nonviolence would change the hearts of their oppressors. The call for patience, love, and peace seemed to them an anemic response to centuries of hatred and brutality. The angry rhetoric of Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and H. Rap Brown was more in tune with the frustration of black youth impatient for change. The critical years of 1963 to 1965 in King’s leadership coincided with the rise of angrier voices in the movement.

I grew up as some of the most catalytic moments in the struggle for civil rights were unfolding. In the year when Emmett Till was lynched, when Rosa Parks sat in a forbidden seat on a bus, and when Martin Luther King Jr. became president of the Montgomery Improvement Association and led the historic bus boycott, I was ten years old. I was beginning high school when federal troops were sent to desegregate Little Rock High School, when the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee was founded, and when lunch-counter sit-ins were beginning.

In the extraordinary year of 1963, I went off to Dillard University, a black college in New Orleans. I chose Dillard because a high school teacher who urged me to go to college thought that I might not be treated fairly if I attended a recently desegregated one in Texas. In that year, Bull Connor’s fire hoses, Martin Luther King Jr.’s arrest in Birmingham, and the systematic harassment of James Meredith at the University of Mississippi led her to believe that attending a black college was a safer course.

There was no refuge from the violence of that era, however; soon after my enrollment at Dillard, that idyllic campus was disrupted by the news of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination. The loss of this president, the very incarnation of hope for so many of my generation, made me fear a bleak future for myself and the country in spite of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which took place just after I arrived at Dillard to start my college education. Notwithstanding the historic crowds and King’s moving “I Have a Dream” speech delivered at the march, the myriad human rights activities and general tenor of the times made it difficult to see the importance of that event or of King’s words.

I had gone off to college fearing that there would be few opportunities for me in spite of my education. It was not unusual for black students of my age to understand and accept all too well the limited range of opportunities available to us after college in spite of the burgeoning civil rights movement. By the time I graduated from Dillard in 1967, a succession of events had intensified black college students’ focus on more rapid progress: the Sixteenth Street Church bombing, the Selma march, the race riots in Watts, the Civil Rights Act, and the executive order establishing affirmative action. King’s stature and relevance seemed to diminish as he broadened his focus to include not only the exploitation of blacks but economic inequality more generally and the war in Vietnam. The movement was broadening and becoming more complex; a range of voices advocated widely varying approaches.

For my part, though I harbored no negative reaction to King, I thought his methods would do little to alleviate the entrenched resistance to change that we experienced on a daily basis and were impatient to address. His “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on August 28, 1963, was certainly moving, but by the time I graduated from college four years later, I had begun to doubt its efficacy.

As I stood in the plaza in northern Spain on April 5, 1968, almost five years later, I was struck as never before by what an important, rare, and effective leader this man had been. Coming from a family of preachers, I had thought of him as a preacher-activist like so many others, but I now recognized that none of them had generated the same degree of worldwide respect. None had espoused a philosophy capable of arousing the same measure of interest and commitment as King’s message of nonviolence. In that distant place, among a people with no connection to the world in which I had been born and reared, King was genuinely mourned.

My recognition of the reach of his message prompted me to pay attention to what he taught in a completely new way. In this, I was not alone. In the wake of King’s assassination, many people came to understand better how King’s exceptional and selfless ministry had shined an unforgiving light on the brutality of bigotry. Notwithstanding the virulent hatred of many, then and now, toward what he represented, he was a giant of his time, and, in death, his greatness could no longer be disputed.

Fifty years after the March on Washington, it is even clearer that his impact on America and on freedom movements around the world will be among the most lasting in history. No efforts to discredit him during his life or after his death have been successful, and I do not believe that they will ever prove so. The meaningfulness of how he sacrificed to achieve a world in which people worked together across race, class, and religion to achieve freedom is unassailable. The brilliant example that he offers today rests upon our understanding of his courageous deeds, but also upon our reaction to his still powerfully evocative words.

An expert in writing will undoubtedly quibble with King’s rhetorical precision, while a stickler for the correct citation of sources may take issue with the originality of his words. King was learned enough to have a critical understanding of how language can enable the unaware or indifferent to gain a better understanding of the suffering and injustice that others experience. He used everything at his disposal to enhance his depiction of wrongs and his exhortation to justice. His “beloved community” vividly encapsulates how he saw the world, with the possibility of reconciliation between victim and oppressor, between those on the sidelines and those in the struggle. As a gifted orator working in the tradition of soaring and mellifluous black Baptist sermons, he was able to convey the virtue and necessity of a virile shared humanity that overcomes historic and current wrongs. It was the only way forward for a nation that had accumulated serious human rights abuses and a suffering community with grievances too deep to remedy through mere political change. His, in short, was the only way toward change and the reconciliation so necessary in its wake.

In the decades following King’s death, the country has seen startling change and civil rights gains too numerous to mention. As the cause of gay rights continues to advance, a significant majority of the country now takes it as a given that all are entitled to basic civil rights, equal pay, and freedom from bigotry. The stunning election of an African-American president has only added to the sense of a changed nation. Our international colleagues ask how President Obama’s election is possible in a country where race is still such an important factor. Martin Luther King’s vision anticipated the fact that political advances alone cannot eradicate the need for a new way of seeing what living in a shared community requires. That new way is powerfully expressed in the “I Have a Dream” speech with its notion that we should join hands and move forward together because the mean and messy act of perfecting the union can be accomplished only if we look beyond our individual grievances and needs.

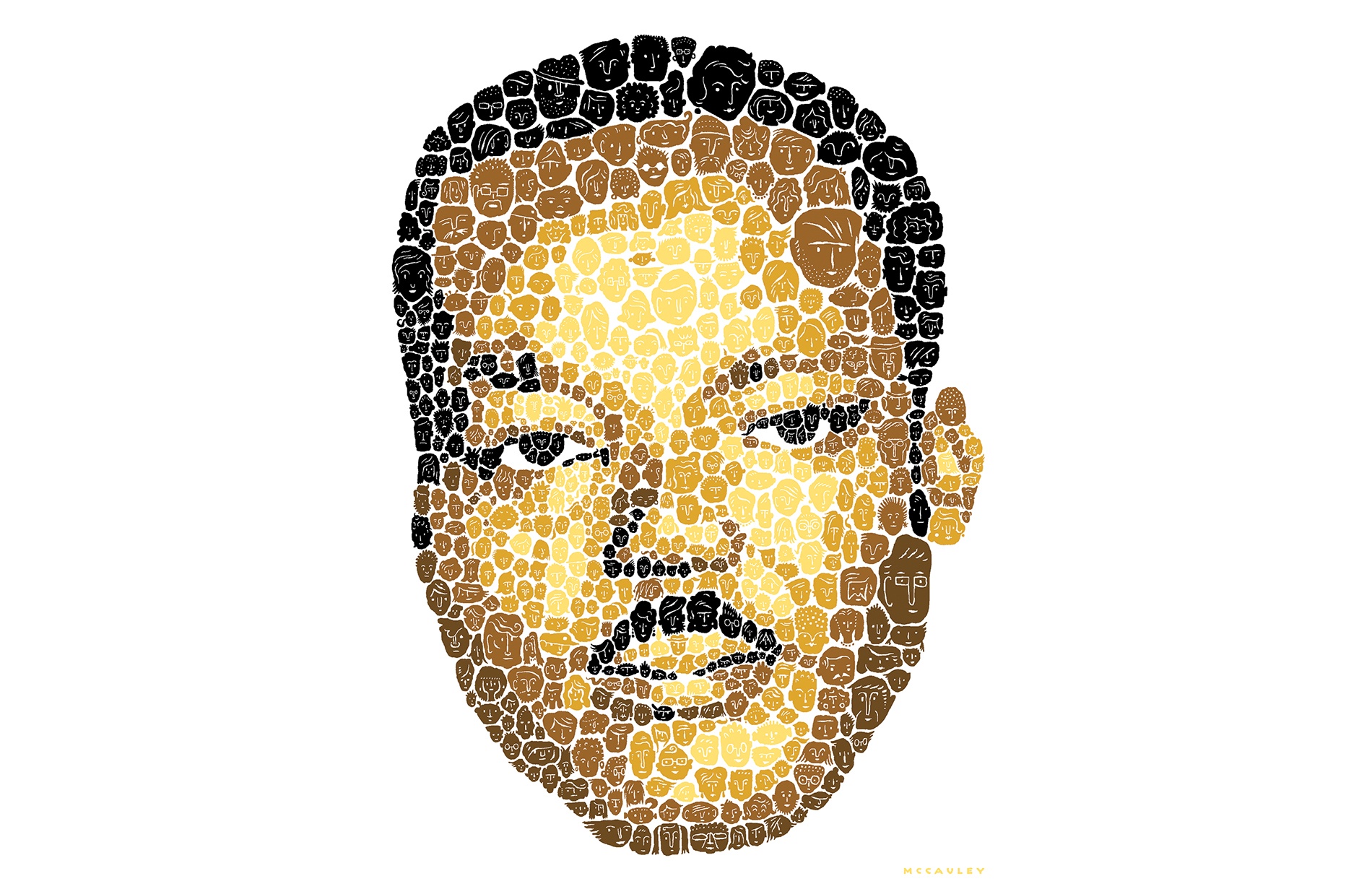

Most who were in Washington the day King delivered his speech would not have imagined the future we have today. Martin Luther King Jr. was able to arouse in millions not only the hope that a more complete freedom could come to pass, but also the awareness that it was important for individuals of good will to participate in making it happen. What Taylor Branch called the “cross-cultural drama” that was the civil rights movement was the decisive formation of a new vision for America in which whites and blacks collaborated in overturning peacefully the injustices of the previous age.

Since that terrible day in 1968 when King was murdered, the “I Have a Dream” speech has taken on new meaning and potency. We reread it and rehear the recording of his voice, recognizing it as one of the most important public addresses given in the modern age, not because of its art but because of what it accomplishes. An anthem of a new America, it is the speech that school children memorize, teachers teach, and activists emulate. In it, King calls us to a prophetic vision of America. It is, for its time, a fantastical and yet grounded ideal that draws one into the important act of imagining a new country. Peopled with individuals of every race and religion, the world he sees is one in which everyone shares the same freedoms and opportunities. Citing the words of a Negro spiritual, he suggests that this freedom can be fully realized only when all are able to sing together, “Free at last!”

In my struggle across the decades to understand my place in American society, these words of Martin Luther King Jr. have provided encouragement and solace. Remembering that sunny day in 1968 when I stood in a Spanish plaza and acknowledged the honor of living in the era of Dr. King, I have drawn hope from the impact he had on the world. In graduate school I pondered how I could commit my life to realizing the world that he saw. I didn’t need to be a gifted orator, a visionary, or a national activist to do my part; focusing on access to education, I realized, could be a way for me to improve on our shared responsibility to create a more equitable world. Especially meaningful to me was the recognition that one could fight for justice for one’s community without abandoning a sense of responsibility to other communities. King understood that both were essential. Over time, I began to imagine a way in which, through education, I could not only teach the lesson of the Beloved Community, I could live it.

While president of Brown, I visited the National Gandhi Museum and Library in India. The modest building welcomes many pilgrims who seek to understand better what made Gandhi the extraordinary visionary that he was. King had visited India and drawn inspiration from what he saw and learned there. When the staff of the library learned of my presence, they took me aside to tell me about Dr. King’s visit to their country and, in particular, his visit to the library. King had been so moved in the presence of Gandhi’s belongings that he asked for and was granted permission to sleep in the building overnight. The staff made a pallet for him on the floor, and there he remained, they said, until the next day.

What must King have been thinking as he prayed and meditated among Gandhi’s books and artifacts? His own essay on his trip to India, “My Trip to the Land of Gandhi,” reveals that visiting India had a profound impact on him. From meeting with Nehru to spending time with Gandhi’s family, he could no doubt see the intimate comparisons between his and Gandhi’s struggle. Writing about this visit in Ebony magazine in July 1959, King observes that, in spite of the skepticism of many supporters, Gandhi’s lasting impact was evident in many aspects of the India that he saw. After being stabbed earlier in Harlem, King would have wondered about the possibility of an assassin’s bullet in his own life while also contemplating how his words and deeds could have a similarly lasting impact in the event of his death. That he might have understood from this trip to India how meaningful his imprint on America would be after his death was, for me, immensely consoling.

His “I Have a Dream” speech will, I believe, remain one of the most memorable orations in our national life. Whenever questions of equality arise, it will be a point of reference not so much for what it depicts about issues of the time but for what it evokes about our possibilities as a nation healed. Nowhere in national life has a more satisfyingly idyllic picture of America been presented.