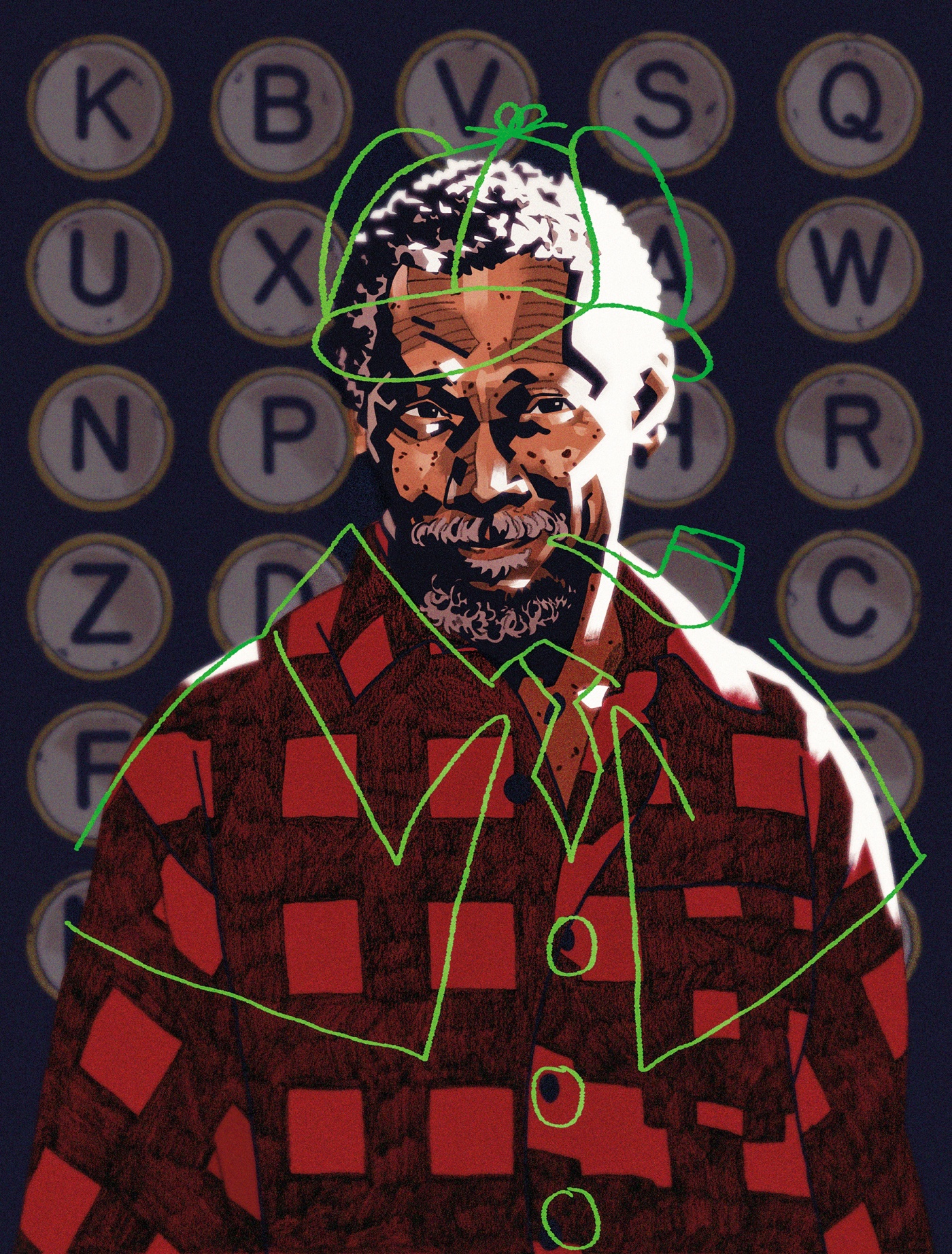

Percival Everett Thinks You’re Smart.

Prolific, multi-talented writer and artist Percival Everett ’82 AM is one of the most celebrated American writers of our era. But when it comes to figuring out what his books actually mean, he prefers to leave that up to you.

Columbia, South Carolina—Soda City, as some locals call it. In no year does the place fail on its “famously hot” reputation, and 1971 is no different. The city saw steady growth the previous decade, and while it’s no Atlanta or even Raleigh, it holds its own as South Carolina’s capital. It’s a decent place for a smart boy to grow.

In a quietish suburb east of downtown, there’s a baseball game going on. The team at A.C. Flora High School isn’t winning the state championship or anything, but the players are working hard. Fastballs buzz through the air like mosquitos. Armpits, barely post-pubescent, are as swampy as the forest when the Congaree floods. One boy, a freshman and fourteen, is in the outfield holding something in his glove. No, it’s not a ball he’s grabbing onto.

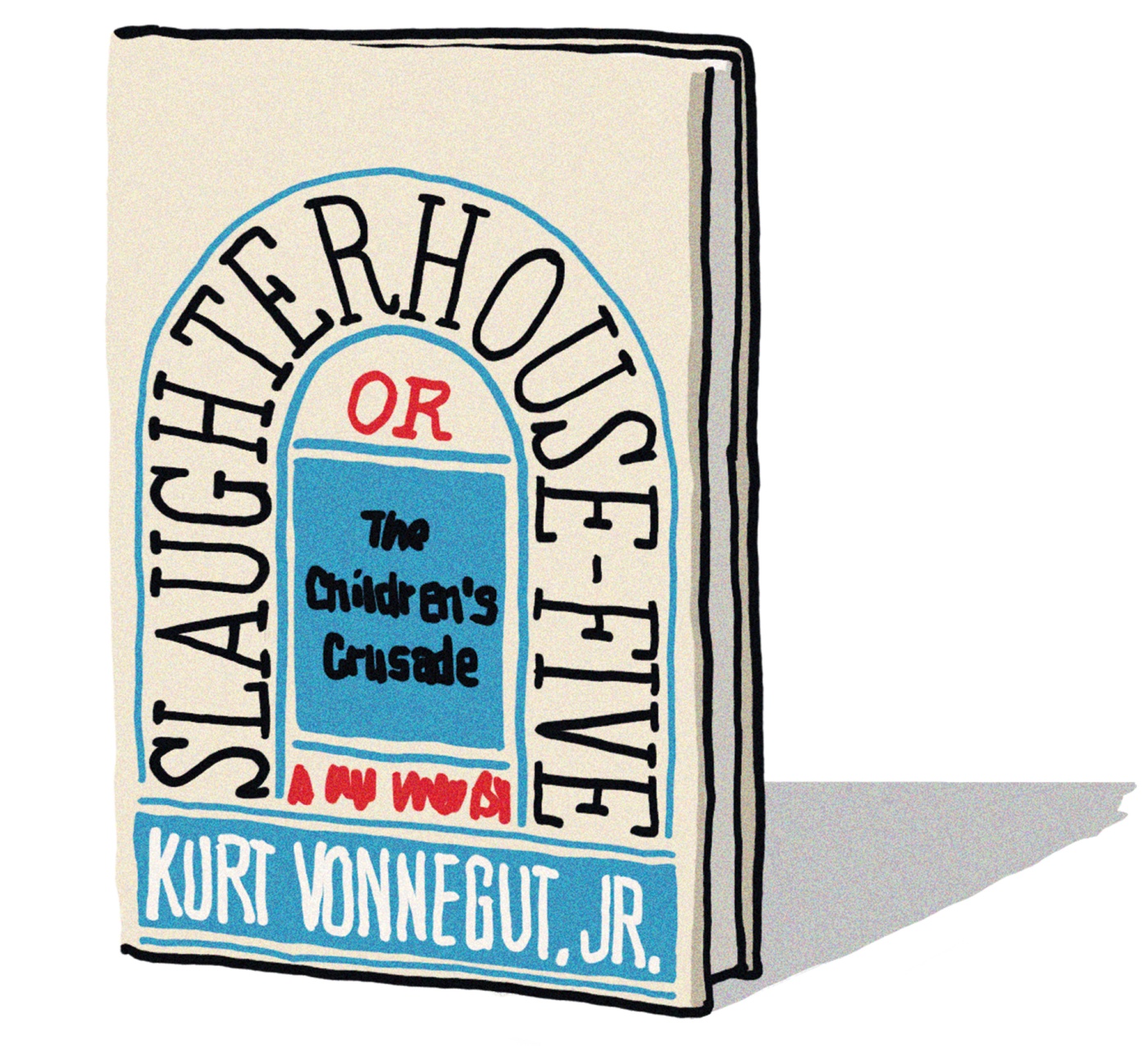

It’s a Kurt Vonnegut novel, and Percival Everett is about to get caught.

In 2023, Percival Everett ’82 AM is a distinguished professor of English at the University of Southern California and a writer with over 20 novels under his belt. In 1971, though, he was just a kid reading during the game, moved from the outfield to third base so his coach could monitor him more closely. Nowadays the anecdote is quite charming, but as Everett says, “I wish the baseball team had thought that.”

He got his love of reading from his father, also named Percival, who, bar Lewis Carroll, didn’t keep children’s books in the house. Young Percival didn’t mind. He liked the idea of reading books that were too old for him, and not even in the smutty sense. Stories like Vonnegut’s, dripping in satire and concerned with heady issues like the threat technology posed to humanity, fostered Everett’s teenaged comprehension of language and life. Maybe he wasn’t catching fly balls, but that’s because he knew there was so much more in the world to grasp.

That thirst towards understanding catapulted him through high school into higher education. Everett set about attending the University of Miami and, always one for a dense read, he studied philosophy—logic, in particular—earning a bachelor’s degree when he was 20 and making headway towards a PhD. At some point, though, the never-ending scholar realized that he had a breaking point; philosophy was too scholastic, no matter how beautiful the proofs of Wittgenstein and Gödel. So what now?

He turned to writing.

The exercise of writing offered Everett new methods with which to explore philosophical issues. “I’m fascinated by the way minds work and the way the changing of them is working,” he says. Everett was drawn especially to fiction, which gave him the opportunity to dream up and explore countless imaginary minds. Seeking an academic landing pad to pursue this new venture, he landed at Brown’s graduate fiction program. As Everett says, “Brown allowed me to really just be who I am and just work.”

Who Everett was was a fairly solitary man who, with the exception of nightly chess matches with professor R.V. Cassill, came to College Hill to write. He left Brown with his first novel in his hands, Suder, which he’d publish a year after graduation. Suder opens with its protagonist Craig Suder batting below .200 because—wait for it—he’s a failing third baseman for the Seattle Mariners.

Right off the bat, Everett found satire fitting for his style, and he wasn’t afraid of pointing it at himself. And in his consequent career, four decades and counting, he would never really abandon that satirical bent, always striking some balance between humor and social commentary. Though at the time a young and mostly unknown writer, Everett seemed to have found some steady footing.

More than just an author

Everett also found steady footing in academia. A few years after graduating from Brown, Everett landed a position as assistant professor of English at the University of Kentucky. Through the 1990s, he’d hop from Kentucky to the University of Notre Dame, then Wyoming, then California at Riverside, finally settling at University of Southern California in 1998.

In fact, since his first teaching position, he hasn’t spent a single year without one, making his prolific career doubly impressive. It mirrors the work of Robert Coover, one of Everett’s greatest influences, whom he met while Coover was a literary arts professor at Brown. Similar to Everett, Coover has written 20 novels, most of which were published during his three-decade tenure at the University, and he explored other forms of writing like short-form fiction and playwriting. “I’m always amazed at not only the depth of his work but the breadth of it,” Everett says.

To his credit, Everett has also traversed far from just the world of novels, having published six poetry books, four short story collections, and an innumerable amount of smaller works—including a children’s book set in the Wild West. His creative career at large also spans editorial work and visual art. In 2021, he presented a solo exhibition of paintings and drawings to accompany his new novel The Trees. In that sense, Everett can’t be labeled as just an author. His creative landscape is vast, intermodal, and interconnected, and we the public may have only a sliver of it on the map.

The inspirations for Everett’s novels are opaque, even to him. “I never really know what generates a novel,” he says. “It always seems like magic to me.” Still, some themes recur in the geography of his bibliography, and as in Suder, some mirror Everett’s actual life (although Everett explicitly avoids writing anything autobiographical). For example, novels like Erasure and Telephone feature professors as protagonists. Even more, the main character of Dr. No, his most recent book, is a (fictional) professor of mathematics at Brown University.

Rolland Murray, a real-life professor in Brown’s English department, points out that Everett’s writing is not fully at peace with the academy. In a presentation on campus titled “Not Being and Blackness” and subsequent article in American Literary History, Murray speaks to Everett’s critical view of the centralization of African American literature, which has become a focus of academia and the literary marketplace since the 1980s. While this process has opened up opportunities for writers like him and Everett (Murray, for one, believes that centralization has been “overwhelmingly quite generative” for Black writers), it does pose new challenges. Everett explores these challenges in Erasure, in which a Black professor of English can’t get his writing published because it is perceived as not Black enough.

Because when it needs academic and capitalistic approval, what Black writing is valid?

“I’ve been called a Southern writer, a Western writer, an experimental writer, a mystery writer, and I find it all kind of silly. I write fiction.”

Everett is not interested in writing toward stereotype. “One of the things I really hate is the presence of characters that... fall into any stereotypic range that supposedly makes it comfortable for the mainstream readership,” he says. “If you don’t have your character comb his afro or cross Lenox and 125th Street, that character is [perceived as] white... It’s perhaps the most racist move that we make in considering stories in our culture.” While a majority of his protagonists are Black, Everett often makes no mention of their race until further into the story—usually after they encounter a white character, as writer Tadgh Hoey notes in a review of The Trees.

And just as Everett believes that the possibilities of Black experience are infinite, he believes the same for his writing. As he said in a 2021 interview with Booth, “I’ve been called a Southern writer, a Western writer, an experimental writer, a mystery writer, and I find it all kind of silly. I write fiction.”

Indeed, Everett’s catalog spans countless genres and forms, and he has made a name for himself in his originality and refusal to repeat himself. On the face of it, it makes him a daunting author to approach. He is more than one of America’s foremost Black writers—he’s proven that he’s far more than just a person of letters in the first place—and his work aims to do much more than assert singular truths. How, then, to read Percival Everett?

Being and Blackness

Soda City—a derivation of Cola, a common abbreviation for Columbia. Columbia is, of course, derived from Christopher Columbus, and perhaps that’s an indication of the mottled civil rights history of the city and the state it represents. The Confederate flag flew on top of Columbia’s statehouse from 1962 to 2000—an act that Everett had publicly denounced far before it stopped—and even when it was removed, it was relocated to a Confederate monument still on statehouse grounds. It remained there until 2015.

“I grew up in the state where the Civil War began,” Everett says. “You know, that affected my relationship to American history.”

Everett’s most extensive engagement with South Carolina politics (at least in his fiction) came in 2004, when he and fellow USC professor James Kincaid published A History of the African-American People (proposed) by Strom Thurmond, as told to Percival Everett and James Kincaid. It’s an epistolary novel following two characters, Percival Everett and James Kincaid, as they ghostwrite an African American history for Strom Thurmond—a United States Senator from South Carolina who, among many conservative initiatives he pursued in his 48 years in the office, conducted the longest single-person filibuster in Senate history, speaking for over 24 hours to prevent passing the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Everett’s politics are largely unwavering in his bibliography, which has consistently put forth incisive social commentary, often on the historical and contemporary persecution of Black Americans. But for much of his career, he has refracted his racial politics through layers of metaphor and irony. As Murray puts it, “He’s always been sly.”

It’s true about any topic Everett writes about. His often abstract and experimental narration rarely suggests a singular dogmatic reading, instead placing the responsibility on his audience to determine what his writing means. “I would never pretend to give an interpretation to a reader,” Everett says. We are not meant to walk away from his books with any specific belief or changed in any specific way.

Murray, however, notices that the way Everett writes about race has changed. Specifically since the mid-2010s, Murray believes Everett’s commentary has confronted the brutality of American racism more directly, coinciding with the surge of racialized violence in the Trump era.

A notable example—especially with the recent death of Carolyn Bryant, who incited the 1955 lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till—is The Trees, set in the Mississippi town where Bryant accused Till of making sexual advances toward her. As in Everett’s book with Kincaid, the work of fiction contends with the very real legacy of American racism. The story imagines a world where a string of white men—starting with the fictionalized son and nephew of Bryant, then more across the country—are murdered. Each crime scene also contains the body of what seems to be an actual lynching victim; one that looks like Till appears (then disappears from) where Bryant’s relatives are killed, as if delivering his retribution from beyond the grave. The Trees is a twisted dissection of justice, which is nothing new for Everett. But this time around, his call for justice is more urgent than ever.

Everett takes a closer look at the revenge narrative in Dr. No. Wala Kitu is a Brown professor who specializes in nothing, and as an expert on nothing, he is hired by supervillain John Sill to help steal nothing to use it for his nefarious purposes. It’s a brutal soup of semantics, but it’s perhaps clearest in this quote from General Takitall, one of Sill’s accomplices: “This country has never given anything to us and it never will. We have given everything to it. I think it’s time we gave nothing back.”

The world of Dr. No means this literally. Sill’s goal is to use nothing to turn other things—including entire towns and the people within them—into nothing. His first choice is to target Quincy, Massachusetts, where he was called a racial slur. Sill’s aspirations towards villainy—which he effectively accomplishes through seemingly endless money, coercion, chemical incapacitation, and eventually murder—is motivated by his parents’ death at the hands of police brutality, targeted for witnessing police and government corruption. At some points, it’s a humorous, Bond-esque caper, but it’s also a serious, albeit slightly fantastical, meditation on what Black retribution could be if it went tit-for-tat.

It’s another way to define the overlap of “not being and Blackness.” Black Americans in the past and present have been consistently reduced to nothing but their race—or reduced to not being at all—and Everett is asking how possibly they can respond.

“I would really love to live in a world where people say, ‘Wow, that’s really difficult to read,’ and it’s an admission of some kind of joy.”

He poses the question, but not a solution. As Kitu begins to realize that Sill’s villainy has tangible, bloody consequences, he begins to work against him. But Sill is never painted as wholly in the wrong.

Novelist Sherman Alexie writes this in his introduction to Everett’s 2003 book Watershed: “Everett knows that the worst of us and the best of us are only separated by the thinnest of moral margins.” In Dr. No, both Kitu and Sill believe that “nothing matters.” Sill runs with the conclusion down a path of chaos and cruelty, but Kitu instead commits to saving others that Sill endangers, even when it endangers him, and even when he doesn’t fully believe it matters. In no brief terms, empathy and inherent human good are at the center of Dr. No’s ethos.

Though, of course, Everett would likely not say it as such.

Percival Everett wants you to read

Percival Everett is a 66-year-old man and he is getting off a plane at LAX. He travels quite a bit nowadays, so he savors the time that he gets at home in Los Angeles with Danzy Senna, a celebrated novelist who also happens to be his wife, and his two children, Henry and Miles.

He’s returning from Yale University, where he presented a lecture this past February. In it, he said that he desires to “press the limits of artifice.” Always one for a dense read, Everett achieves his characters’ authentic voices of knowledge on disparate fields by immersing himself in relevant texts. He acquired a small library on lynching while writing The Trees, and in Dr. No, with the way he drops terms like “terminal regress” and “metastable vacuum,” you’d expect him to be, well, a former philosophy doctoral student. He can become a convincing “lay expert” on seemingly anything he writes about, and that is nothing short of brilliant.

The American literati are beginning to recognize this brilliance more and more. Little over a month after his lecture, Yale announced that Everett was a 2023 recipient of the global Windham-Campbell Prize, whose previous winners include influential names like Cathy Park Hong and former Brown literary arts professor Renee Gladman. Among many other honors, he was also a 2021 Pulitzer Prize finalist for Telephone, and he earned a spot on the 2022 Booker Prize shortlist for The Trees. “His success and visibility in recent years,” Murray says, “is really an indication of how expansive the field of Black writing has become.”

Everett still maintains his humility, though. When asked how he came up with the idea for Dr. No, he says, “I have teenagers, so they’re always telling me that I don’t know anything. And so I just went with that.” He’s not just being facetious. He admits that he sometimes understands “very little” of what he writes about, and that writing Dr. No was a push for him to address topics he wanted to understand better.

He recounts a moment with the late Howard Pospesel, one of his philosophy mentors back in Miami. “I remember one day we were discussing Gödel’s proof, and he leaned back in his chair and he looked at the ceiling and was genuinely and happily confused. And I remember thinking, ‘That’s where I want to be.’”

Percival Everett wants you to read. He says reading is the most subversive thing that anyone can do. But perhaps even more so, he wants you to push yourself in your reading.

“I keep asking the world, ‘Where are the-14-year-olds that are going to read my novels?” he quips. Admittedly, his texts are not the most accessible to 14-year-olds, or really anyone of any age, but he believes that the challenge of reading is the key to progress. His 14-year-old self is a testament to it. “I would really love to live in a world where people say, ‘Wow, that’s really difficult to read,’ and it’s an admission of some kind of joy,” Everett says. “That work is not calling you stupid because you don’t get it right away. What it’s doing is saying, ‘You are going to participate in making this meaning,’ and that you are as smart as the work.”

So if you’re reading Everett, believe that you’re as smart as he is. Because he does.

Ethan Pan ’22 is the assistant food editor at 5280 Magazine. He currently lives in Denver.