The six alumni honored on the following pages were killed as a result of the terrorist attacks of September 11. Fortunately, no immediate relatives of current Brown students died in the attacks and their aftermath. We do know, however, of at least eleven alumni--Finn Caspersen '63, David Filipov '84, Kathleen Kauth '01, Patricia Keating '80 Ph.D., Bonnie MacDonald McEneaney '76, Judith Bram Murphy '81, Amy Dana Profaci '86, Joseph A. Profaci '86, James M. Roger '98, Thomas H. Roger '69, and Abigail D. Ross '98--who lost members of their immediate families in the tragedy.

Donald F. Greene '71

No one knows exactly what happened on board United Airlines flight 93, but the people who know Don Greene are certain he died a hero.

Greene, the father of two children, was on his way to meet four of his brothers in Lake Tahoe, California, for a hiking vacation when the hijacked plane crashed in rural Pennsylvania, less than two hours after takeoff. His family believes that Greene, a college wrestler and an experienced pilot, was among the passengers who tried to overtake the hijackers, possibly averting a greater tragedy. While Greene was not certified to fly a 757, according to friend and colleague Peter Fleiss, there’s no question he could have landed it safely.

"We don't know precisely what occurred," says his sister Terry, "but we all know he's extremely capable--a determined leader and not somebody to shirk responsibility." His wife, Claudette, says that no matter the circumstance, her husband always did the right thing. "Anyone who knows this guy," she says, "knows he was involved at some level, somehow."

Greene, ironically, had devoted his career to aviation safety. He was executive vice president of Safe Flight Instrument Corporation, which his father founded. The company invents and manufactures stall and wind-shear warning devices. "He ran the whole operation," says Fleiss, who describes Greene as an expert negotiator and a quick-witted manager of the company's 150 employees.

But Greene took most seriously his job as father to ten-year-old Charles and six-year-old Jody. "I used to walk with Don every day at lunch," Fleiss says. "Occasionally we'd talk about business and occasionally we'd talk about politics, but usually he wanted to talk about his kids." Fleiss would hear every detail about how Jody performed in her school play or how Charlie was doing on the ski slopes. When Terry Greene visited the office, her brother would marvel over photographs of Charlie and Jody and declare, "Aren't I lucky!" Whenever possible, he'd leave work to attend a school performance or a 2 p.m. book-report presentation. "He was always there, always positive, very involved with the kids as a dad, a friend, and a mentor," Claudette says.

The fifth of twelve siblings, Greene was the one on whom all the others leaned. When Terry was battling breast cancer, Don and their father took her on an island-hopping flight. "He was so stable," she says. "He consistently liked to do nice things for other people, liked to be dependable. He'd probably be the first person we'd call in an event such as this."

At Brown, Greene concentrated in engineering and was a member of the wrestling team. He received his M.B.A. from Pace in 1983. A certified pilot before he could drive, he also raced sailboats. He interviewed prospective students for BASC.

In the days following her brother's death, Terry Greene wrote a letter to the editor of the Boston Globe asserting that while future terrorist attacks must be prevented, "the last thing that our family wishes to see are any more innocent lives lost and their families torn apart out of panic, misplaced anger, or hateful prejudices. These are not American values." She wrote the letter with her brother in mind. "I feel like what Donny did was heroic because it was out of compassion and the best of American ideals" she says. "I didn't want that tainted by blind calls for revenge."

Donations in Greene's honor may be made to the Alliance of Breast Cancer Organizations, 9 E. 37th St., 10th floor, New York City 10016, or to the Corporate Angel Network, Westchester Airport, 1 Loop Rd., White Plains, N.Y. 10604. In addition to his wife and children, Don is survived by his father, Leonard; his stepmother, Joyce; seven brothers; and four sisters. —Emily Gold

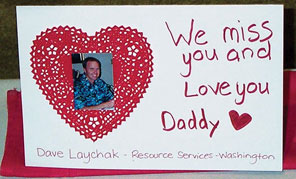

The three things Dave Laychak liked best about his life were his wife, Laurie; their nine-year-old son, Zachary; and their seven-year-old daughter, Jennifer. The four were inseparable, Laurie says, especially on weekends, when they'd pile into the car for a "family-fun excursion" to a Civil War battlefield or a national monument. "He loved being outside with the kids, playing football, going on nature walks, just being a kid himself," she says. "He seemed happiest at those moments."

Dave Laychak, a civilian budget analyst for the U.S. Army, was in his office on the first floor of the Pentagon's outer ring when hijacked American Airlines flight 77 exploded into the building. "It was chilling when we looked at the charts to see where the plane went in," Laurie says. "He was literally at ground zero."

Dave and Laurie met at the Pentagon in 1984, when Laurie was also working there. They were among the few young people in the office. Perhaps because they were both from military families, they quickly became friends and fell in love a year and a half later. "He just had a gentle soul," Laurie says.

The Laychaks moved to Sierra Vista, Arizona, in 1992, when Dave was hired as a budget analyst at Fort Huachuca there. They loved the Southwest--the open space, the mountains, the small-town living--but when Laychak was offered a promotion at the Pentagon last year, they returned East. They chose to live in Manassas, Virginia, even though it's almost an hour away from the Pentagon, because the area is near open space. The move East also brought the Laychaks closer to Dave's family, as well as to better schools.

Weekends were Laychak's happiest times. A good teacher who genuinely enjoyed the company of kids, he was the coach of Zachary's soccer, basketball, and baseball teams. "We were always hearing people request him as their coach," Laurie says. "He was just so patient. He always had a positive thing to say about everybody." During the family's weekend excursions to Virginia's many historical sites, she adds, Dave liked to entertain the family by singing "God Bless America" in the car. "He was just such a great patriot," Laurie says. "I think this is what's going to help me and the children get through this. He loved our country and our freedoms. He saw working for the army not as a job but as something he could do to serve our country."

At Brown, Laychak was an organizational-behavior concentrator, a member of Delta Tau, and a defensive back on the football team. He was a starter during his freshman year, but a shoulder injury limited his playing time for the next three seasons. During his senior year, though, he was one of the few non-starters to stay with the team. "He came and kept practicing, never complained, never felt like he got a raw deal," recalls his former teammate Dan Bauk '83. "That says a lot about his love of the game."

Laychak was also the "self-appointed activity director for the campus, remembers Dan Nelson '83. He was a constant jokester, Steve Brown '83 recalls, always ready to do "goofy, off-the-wall things." "I considered him my best friend," Brown says. "I would assume there were a couple others who also considered him their best friend. That's the kind of guy he was." Now Laurie Laychak worries that her children's memories of their father will fade with time. She asks Dave's friends to write down their memories of him and send them to her so that Zachary and Jennifer can remember him vividly. Their address is 13089 Dove Tree Ct., Manassas 20112. Donations may be sent to the David W. Laychak Memorial Fund, c/o Navy Federal Credit Union, 2898 Dale Blvd., Dale City, Va. 22193 —Emily Gold

Charles J. Margiotta '79

Charles Margiotta, a lieutenant with the New York City fire department, was driving home to Staten Island after a twenty-four-hour tour in Brooklyn when from the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway he saw smoke pouring from One World Trade Center. A firefighter for twenty years, he reacted instinctively: he sped over the Verrazano Narrows Bridge to find a company he could help. Margiotta pulled into the Rescue Co. 5 station right off the bridge and jumped on a truck leaving for the World Trade Center.

After arriving at the towers--according to Margiotta's family, Rescue 5 was one of the first companies to respond--Margiotta called his mother, Amelia, to tell her he was working with Rescue 5. "It's bad and I don't want to be unaccounted for," he said. The two exchanged expressions of love, and then within minutes Margiotta and ten members of Rescue 5 were trapped inside as the tower collapsed. All are listed as dead or missing.

Margiotta's family says that his rush to help was typical of him. Bruce Alterman '79, Margiotta's best friend since their days at Brown, remembers the many times when the two of them would be late for a meeting or dinner because Margiotta insisted on pulling over to help someone fix a flat tire or to help a woman load groceries into her car. Alterman said Margiotta had a habit of getting into fights to defend people, usually strangers, who he thought were being picked on. "He had a big heart," says Margiotta's father, whose name is also Charles, "but believe me, don't cross him--he'd beat the hell out of you."

Those who knew him well saw in Margiotta a dedicated family man. "He was our strength and our hero," Margiotta's father says of his son, who this year celebrated his fourteenth anniversary with his wife, Norma. "He was the guy all the family turned to." Margiotta often took his son, Charles, eleven, and daughter, Norma Jean, thirteen, hunting and fishing and volunteered as the athletic director at their school.

Standing five feet, eleven inches, weighing 230 pounds, and sporting a dark handlebar mustache, Margiotta stuck out at Brown, Alterman says. He played offensive guard on the 1976 Ivy League champion football team and was a good student who had friends from many different social circles. After graduating with an A.B. in English and sociology, Margiotta went to work as an executive for General Motors, but he quickly chafed at the desk job. "He never wanted to be a suit-and-tie guy," his brother, Michael, says. And so he joined the Fire Department of New York.

For most of his career Margiotta worked at the 128th Street firehouse in Harlem, one of the busiest companies in the city. He transferred to Staten Island five years ago to be closer to his family. In addition to his firefighting duties, Margiotta occasionally worked as a substitute teacher in special education classes around New York City. His love for adventure led to stunt work on such movies as Malcolm X and King of New York. He also landed several minor acting roles, appearing in Frequency and Kiss of Death and the television series Law & Order. "He sounded like he gargled with gravel," Alterman recalls, "especially over the years, [after] breathing in all that smoke."

In the months before the attacks, Margiotta had been helping to organize the November 10 reunion of the 1976 football team. He is scheduled to be honored that weekend during the football game against Dartmouth.

Margiotta's family can be reached at 463 Ingram Ave., Staten Island 10314. Friends have set up a fund to benefit Margiotta's wife and children. Contributions can be sent to the Charles J. Margiotta Family Trust, 251 Edgerstoune Rd., Princeton, N.J. 08540. —Zachary Block '99

Raymond Rocha was eight years old when his mother went blind. Though he was only in third grade, he quickly learned to do such grown-up chores as checking her bank statements and helping her prepare dinner. Later, he would give his mother such detailed descriptions of the movies he'd seen that she felt as if she'd seen them herself. "He was my eyes," says Ann Rocha.

Now she's lost her sight for a second time. Raymond Rocha, a bond trader for Cantor Fitzgerald on the 105th floor of One World Trade Center, is one of 700 Cantor Fitzgerald employees presumed dead from the impact of hijacked American Airlines flight 11 on the trade center's north tower. He had been working there for only a month.

When Ann Rocha remembers Ray, who was the youngest of her five children, she remembers his kindness. He still called her every day. When he was home, he'd often carry bags for her elderly neighbors. And he had an unforgettable smile, which he flashed at perfect strangers. He was always ready with a "How are you today?" for a supermarket cashier.

Rocha's father, Manuel, is a carpenter who worked long hours to put his children through school, and Ray didn't disappoint him. In high school Ray was an honors student and played football. He tutored classmates for the SAT when he brought them home for dinner, and he chose Brown in part because his mother felt nervous traveling on country roads to Dartmouth. "My Raymond," she recalls, "he never argued with me, and he never answered me back. I was always very happy in his company."

At Brown, Rocha concentrated in business economics, played football, and pledged Delta Tau. One measure of his friendliness was that he'd gone to twenty-eight weddings in the past three years. "He put a lot into twenty-nine years," his mother says. "You know how some people have tempers and show disagreement about everything? He never moaned and groaned. Every day was a new day, and he accepted new challenges."

Rocha had moved over the summer from the Boston suburbs to New Jersey, where he lived with his girlfriend. He loved his new job at Cantor Fitzgerald. "I think it was the high intensity," Ann Rocha says. "He thrived on it." He also loved sports, she says, taking every opportunity to run, toss a football, or play hockey. "He was gifted with speed, agility, concentration. And discipline."

In addition to his parents, Rocha is survived by two brothers and two sisters. The family can be reached at 107 Porter St., Melrose, Mass. 02176. —Emily Gold

The phone rang on the West Coast before dawn: "Mom, I know it's early, but you're going to see this on the news, and I don't want you to worry. I'm in the other building. And I love you."

The caller was Paul Sloan, who worked on the 89th floor of Two World Trade Center and who had just felt the building shake as American Airlines flight 11 exploded into the tower next door. Over the next several minutes he called friends and relatives, telling them he was being instructed to stay put, that debris was falling and it was not safe outside. But while Sloan was on the phone with his sister in New York, the line went dead.

Sloan is presumed to have died after hijacked United Airlines flight 175 was flown into his building. He worked in the research department of the investment-banking firm Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. He'd moved from the San Francisco Bay area about a year ago to take the job.

Those who knew Sloan best remember his discipline, passion, and loyalty. "Paul was very methodical," says his mother, Muffy. "He thought everything was black and white, right and wrong. No matter how hard it was, he chose to do the thing that was right." Among his siblings--he had a sister and two brothers--Sloan was the "glue that held everyone together," his mother says. He played a similar role among his friends. "He was the most sincere, caring person I know," says Jason Wargin '00.

Wargin was a freshman when he met Sloan, then a senior concentrating in history. Both were offensive linemen on the Brown football team and members of Delta Tau. "Paul was a big fish in a little pond," Wargin recalls. "He represented everything I wanted to be as a student athlete." Last year both started new lives as young, ambitious, single New Yorkers. "We were both little fish in a big pond," Wargin says. "When we went out, we went out together--to the park, ballgames, bars, restaurants.

Eugene Inozemcev '97, another teammate and Delta Tau brother, remembers Sloan as a strong athlete and a passionate music fan. But most of all, says Inozemcev, "He'd go out of his way to help you."

On August 18, Wargin hosted a barbecue for Sloan's twenty-sixth birthday. One of the guests was Raymond Rocha '95, a football player and Delta Tau brother who would also perish in the terrorist attacks three and a half weeks later. "I think that was the last night we were all together," Wargin says.

Wargin called Sloan after the first plane hit. "I just got sick to my stomach," he says. "I said, 'Paul, are you okay?' He was calm. He said, 'Yeah, I'm fine.' He said, 'Jay, I need to call my mom.'"

After three days in front of the television waiting for news, Muffy Sloan, her husband, Ronald, and the couple's two other sons drove to New York City. "We just couldn't stay here anymore," she says. Wargin and Inozemcev had been calling hospitals, checking survivor lists, and e-mailing pictures of Paul. But eventually there was no denying the truth. "It's a great loss," says Wargin. "But he's not gone. He'll never be forgotten."

Sloan's parents can be reached at 75 Verissimo Dr., Novato, Calif. 94947. They've set up a memorial fund in Paul's name at the Brown Sports Foundation, Box 1925, Providence 02912. —Emily Gold

On September 11, Joanne Weil '84 was just beginning to feel settled as an attorney at the firm of Harris Beach. By the end of that Tuesday, however, after hijacked United Airlines flight 175 had rammed into Two World Trade Center where the firm's 113 staffers had been working on the eighty-fifth floor, Weil would become known as one of office's five employees missing and, later, presumed dead in the attack. She'd worked there just over a month.

Weil's mother, Judy, says that her daughter, a 1991 graduate of the Syracuse University College of Law, chose the law for its mental challenges. Irwin Kishner, a partner at Herrick, Feinstein, where Weil served as the firm's securities law expert before joining Harris Beach, described her as an excellent all-around attorney. "She was outspoken and extremely intelligent, with a real capacity to pick up difficult subject material quickly," he said.

But the long hours of a lawyer were less enjoyable to Weil, and according to her family she had been tiring of the New York City rat race. She had even been considering a move to Arizona to work for a friend's company, but her family was in the New York area, and she was reluctant to leave them. Weil's parents learned the extent of their daughter's commitment to the family in a letter they received from from one of Joanne's former colleagues after her death. The letter recounted how, after graduating from Brown, Weil had applied to work at a government intelligence agency, an application that Joanne told her parents had been rejected. In fact, the former colleague wrote, Weil had been informed that if she worked at the agency, she would at times be prohibited from telling her family of her whereabouts. As an only child, the letter went on, she couldn't agree to that.

According to Weil's relatives and friends, she was a constant source of support, always ready with emotional, physical, and even financial help. But she was tough-minded and candid as well, says her cousin Jennifer Nelson: "She didn't mince words." Jennifer's brother, Jonathan Nelson '90, remembers Joanne's great sense of humor. "She had an infectious laugh," he recalls. "It started with a giggle and then turned into a laugh, and you couldn't help but join in."

During her free time, Weil made jewelry from antique glass and beads. She loved to travel and took an annual "pilgrimage" to Mexico, her parents say. Weil was also a passionate New York Giants fan and would often watch the games while talking on the phone with her father, Floyd '54.

A French concentrator at Brown, Weil continued to speak French fluently in the years after her graduation. Robin Husney '84 says she would often call her former roommate for help with crossword puzzle clues involving French. "I still can't believe it," says Husney. "I kind of expect the phone to ring and hear her say, 'Hi, they found me.'"

Weil's family can be reached at 20 Birch Grove Dr., Armonk, N.Y. 10504. —Zachary Block ’99