The e-mail that changed Doug Ulman’s life arrived in the fall of 1997:

Doug, yesterday I received an article (from the Brown Alumni Magazine) in the mail from a friend of mine. After reading the article and relating to...what you have gone through, I decided to drop you a line. Being a young man in the prime of your life both athletically and physically then to be struck by cancer is devastating. As you alluded to in the article, cancer is a life-altering event and a rough road. But I feel as if we are the lucky ones. Nobody can really have the perspective and the focus of a cancer survivor. If there is anything I can do to help your cause, please let me know. Otherwise, look after yourself and take care.

The e-mail was signed Lance Armstrong.

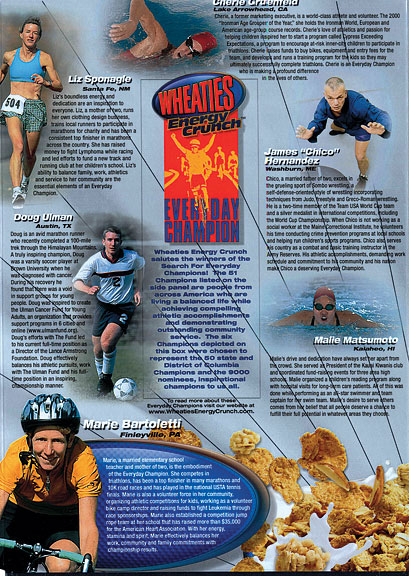

Ulman '99, then a junior, had been the subject of the BAM article, which detailed how a routine chest X-ray had revealed a tumor attacking the cartilage in Ulman's ribs. As an athlete recruited to play soccer at Brown, Ulman had found himself suddenly unable to play the sport that was his passion. Although he loudly cheered his teammates from the sidelines, Ulman, who went through three separate rounds of treatment for bone cancer and melanoma over the next year—including the removal of a portion of the affected rib—was determined to play again. He returned to competition briefly, but ultimately turned his attention to a new challenge.

Ulman's experience with the disease revealed to him how little support existed for young adults facing a cancer diagnosis. "I needed to talk to someone else my age who'd had cancer," he told the BAM, "but I didn't know anyone." With the help of his family and a Royce fellowship, he founded the nonprofit Ulman Fund for Young Adults With Cancer. He set up a website and organized a celebrity auction and a charity soccer game. During his sophomore year, he completed an independent study that allowed him to produce pamphlets aimed at helping young people find information on different cancers and deal with the roller coaster of emotions that follows a diagnosis.

All of this caught the notice of Armstrong, who in 1997 was not yet the celebrity athlete he has since become. Just a year earlier he'd dropped out of the Tour de France and a few months later was diagnosed with testicular cancer. In 1997 Armstrong's first Tour victory was still two years away, and accusations of doping were seven years into the future. More importantly, perhaps, the Lance Armstrong Foundation, whose yellow Livestrong wrist bands have since become ubiquitous, had not yet become the iconic brand that it is today.

Although Armstrong was the public face and the driving force behind the foundation, it would take an organizational mastermind to create its enormous success, a president and CEO who could take it from a small startup to an international force. Armstrong found that mastermind in 1997, when he hit the send button on his e-mail to Doug Ulman.

At Brown, Ulman remained outwardly upbeat during his cancer treatment, but he felt alone. He was either too old or too young for every support group he could find. His classmates were encouraging, but Ulman could see their discomfort with someone whose presence was a reminder that none of them was invincible after all.

"Everybody around is so unsure of what to do that they either won't talk to you, or are very solicitous," recalls Professor Emeritus of Engineering Barrett Hazeltine, a mentor to Ulman during this time. Ulman used to tell Hazeltine, "Nobody seems to know how to treat me. I'm really on my own."

Ulman threw himself back into the soccer team, attending practices even when he was too sick to play and screaming enthusiastically from the sidelines during games. He had always wanted to be a teacher and a soccer coach, so he enrolled in the Undergraduate Teaching Education Program, and did his student teaching at Seekonk Middle School.

"It was awesome," he says. "I loved it. I loved being around kids." He worked with Hazeltine on a series of independent studies, studying such topics as nonprofit management and finance. After graduation he won an Echoing Green Fellowship, which provides two years of salary and health insurance to young entrepreneurs. He left teaching and moved back to his parents' house outside Baltimore to run the Ulman Fund full time.

But before he made that move Ulman flew out to Austin to meet Armstrong, with whom he'd been exchanging e-mails off and on for two years. When he showed up at the Lance Armstrong Foundation's Ride for the Roses in 1999, the cyclist was so busy the two barely had a chance to shake hands. The event included a cancer symposium, and when the speaker opened up the floor for questions, Ulman's arm shot up. He talked about the Ulman Fund and about the overlooked needs of young adults with cancer. He was so convincing that the Foundation invited him to a meeting in Chicago later that year. The meeting included the leaders of most major U.S. cancer organizations, each of whom had fifteen minutes to address how their work might fit in with the Lance Armstrong Foundation. The room was filled with executives in their forties and fifties. Ulman had just turned twenty-three.

The following October Ulman was visiting his then-girlfriend in San Francisco when Armstrong phoned. He was in the Bay Area for a few days and wondered if Ulman would join him for dinner. Their conversation over that meal turned into a five-hour discussion about all that Ulman and Armstrong might accomplish if they joined forces. Two months later Ulman moved to Austin to become the Lance Armstrong Foundation's fourth employee.

The Foundation was still a tiny organization struggling to find its place. Its three employees, who were motivated by a vague mission of helping people with testicular cancer, had little management experience. Armstrong has since written on the foundation's blog: "We thought we'd put on a good bike ride, donate a few thousand dollars to those doing research, and see where else we could help out." However, partly as a result of the Chicago symposium, the board had identified a niche that Ulman would ultimately help grow into a movement. He was hired as director of survivorship services. "Everybody's doing research," Ulman says the board had decided. "Let's figure out something else. Let's not put all of our eggs in the sort of basket that's ten years or twenty years off. How do we help people today?"

Since that time, the primary focus at Livestrong (as the foundation is more familiarly known), has been "survivorship." The idea is not only to survive cancer; beating the disease is a cause for celebration, for living a fuller, more active life. When I visited Ulman in Austin, his assistant drew up a list of Livestrong employees that Ulman wanted me to meet during my visit, and he was quick to point out who among them were cancer survivors. Each of them, he said, was "phenomenal," "unbelievable," or "awesome."

These are adjectives Ulman uses often. He is almost preternaturally energetic and optimistic. He likes to say that his staff is "naíve and audacious," and explains: "We're naíve enough to think that we are going to change the world. And we are audacious enough to try." To the Livestrong staff, he is simply Doug. They joke that in a typical day Ulman can run a marathon in the morning, meet with world leaders before lunch, solve all the world's problems by early afternoon, and throw a party for Livestrong's donors in the evening. "We all wonder how he sleeps," says Rebekkah Schear, Livestrong's program manager for international programs.

Ulman has short brown-blonde hair, squared sideburns, and striking green-blue eyes. He is tall and lean, and his physique reflects the fifteen marathons he's completed and the 100-mile course in the Himalayas he's run. He says he's in better shape now than he was back at Brown. The culture around the Livestrong office encourages this sort of athleticism: there are yoga and Pilates classes for employees, a workout room with Livestrong-branded spinning bikes, and showers in the bathroom for those who bike to work.

Located on a prominent corner in the working class but quickly gentrifying Spanish-speaking neighborhood of East Austin, the organization's LEED-gold headquarters is spacious and airy. Dozens of pieces of artwork from Armstrong's personal collection are displayed around the building, and every employee—including Ulman—has an identical low-walled cubicle. The walls of the conference rooms are either glass or slatted wood. The layout was the geography of collaboration. When the foundation bought and renovated the building—they moved in during 2009—Ulman says, "We tried to make it a startup feel. There's never a meeting where you don't know who's in it."

The atmosphere at Livestrong is both intense and playful. When I visited in November, Ulman was sporting a horseshoe-shaped mustache. During that month—known as Movember to participants—men grow mustaches to raise money and awareness for prostate cancer and other men's health issues. This year the "Mo Bros" raised almost $14 million throughout the United States, 35 percent of which went to Livestrong.

Livestrong has only ninety employees. Ulman frequently uses the words nimble and impact, as in "We want to be the small, nimble group that can attack these problems when we see them." And: "Our goal is not to be the biggest. It's to have the biggest impact. If we can use Lance's visibility, the Livestrong brand's presence, to bring people together to accomplish things that none of us can do on our own, that's the best use of our energy."

"It's been a wonderful thing," Hazeltine says, "how somebody Doug's age took an organization really struggling to find a purpose and a mission and put together an organized, directed, well-managed social enterprise. He really matured the organization remarkably effectively—and remarkably quickly, too."

Hazeltine, who has taught courses in entrepreneurship and organizational management at Brown for fifty years, has seen many nonprofits come and go. Lots of nonprofits, he says, were started by someone able to grow an organization until it employed ten or fifteen people but "then just simply couldn't make a larger impact because they just weren't ready to do the planning." What Ulman has been able to do, he says, is to accomplish the detailed work of identifying opportunities and focusing on realistic goals.

One of those opportunities has been helping patients live with cancer. At the front of the Austin headquarters is the organization's Patient Navigation Center, a series of cheerful rooms where professional "Navigators" help people affected by cancer deal with their diagnosis and its complications. The navigation model was pioneered by a surgeon named Harold Freeman, whose Patient Navigation Institute was the first of its kind when it opened in Harlem in 1990.

Ulman remembers vividly when Freeman—now a member of Livestrong's Board of Directors—gave him and Armstrong a tour. As they passed a series of exam rooms, Ulman says, "He stops us and he says, 'These people represent the difference between what we know and what we do. Millions of people in our country and around the world die needlessly because we don't apply what we already know.' So it started us on this whole path to figure out: if we didn't do any more research—no more biomedical research—how many lives could we save with just what we know works today?"

Navigators at Livestrong help patients get access to the treatments that medicine already offers. "A lot of the people who show up, they don't have transportation," Ulman says. "It's not that they couldn't get treatment, but they may have skipped treatment yesterday because they couldn't get there. Or they didn't have child care. This Venezuelan woman walked in the other day with $7,000 in [medical] bills. She didn't know what to do. It took our navigators maybe fifteen minutes to realize that she was eligible for a federal program that took $5,500 off immediately."

Chris Dammert, director of the Navigation Center, remembers one client who came into the Center with her four-month-old daughter. Her doctors had told her that treatment for her breast cancer would make it impossible for her to have children. "Because of our program, she and her husband were able to afford fertility preservation," Dammert says. "So they froze embryos, and her sister-in-law acted as a surrogate and carried the baby."

Dammert, who came to Livestrong from the for-profit world, wears a dark suit and dark glasses, and his face betrays little emotion. But his voice catches as he recalls this woman bringing in her baby. "And she said, 'Thanks to you, we have a family. Otherwise, we wouldn't have been able to afford it, and we wouldn't have done it.'"

It's a Monday evening at the Four Seasons Hotel in downtown Austin, and Doug Ulman is tweeting. He wears a trim black suit with a blue-and-white checked shirt. Seeing so many partners and great friends at the @cprittexas dinner, he thumbs on his Blackberry. Social media sites like Twitter and Facebook have "changed everything we do," Ulman says. "For a nonprofit, it is a free way to communicate in real time with people who self-select to get the information you're putting out there." More people with cancer are now referred to the organization through Facebook than from any other source.

Ulman and a handful of his staff are at the third annual dinner for the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), an organization established in 2007 with a $3 billion Texas state bond initiative. The idea was to provide $300 million a year for ten years so researchers and scientists could make Texas a cutting-edge center of cancer science. In Texas, however, incurring debt requires a constitutional amendment, which is difficult to get in a state known for fiscal conservatism. Ulman and Livestrong actively campaigned on behalf of the amendment. Getting it passed, Ulman says, "took every ounce of our energy and being. But I loved it."

The CPRIT campaign, he says, was "an example for us as an organization. I think we spent $800,000 on this effort. We got $3 billion! And it doesn't come to us. We don't care. It's not about us. It's about: what's the biggest leverage? A lot of people on our board are entrepreneurs and venture capitalists, and they're all about taking risks and trying to have the biggest impact. We feel like that's somewhat of our sweet spot."

This evening's keynote speaker is Tachi Yamada, former president of the Global Health Program at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. He talks about the importance of making sure funding leads to real results. Quote of the night, Ulman tweets as Yamada speaks. If you aren't keeping score you are simply practicing. Yamada talks about the "crazy, out-of-the box" ideas his program has funded over the years, ideas that would never get by peer review. That doesn't matter, Yamada insists, and Ulman mouths his next line along with him: "Because true innovators have no peers."

Ulman leans over to his colleague Andy Miller. "He uses that line every time," Ulman whispers. "Because it's true!"

At Livestrong all employees are encouraged to spend up to ten percent of their work time on a creative project of their choosing. Last year, for example, Miller decided to work with the cooks at Canyon Ranch to create a cookbook for people with cancer. This year, Rebekkah Schear is using her creative time to plan a musical comedy revue, a revue that will include a staff roast of Ulman.

Ulman loves this kind of creative thinking, whether it serves the organization's mission directly or not: "If someone comes up with a great idea—or even an idea—we should start at yes, and work through every reason why we can't do it. We never start at no. I can't stand when people are like, 'No, we don't do it that way.' Let's try! A venture capitalist funds fifty companies, and if two of them make it they hit the jackpot."

When an employee who had served in the Peace Corps approached Ulman with the idea of expanding Livestrong's mission to include international work, Ulman gave her $100,000 and one year to conduct research. As a result of this one employee's enthusiasm and interest, the organization has thrown itself into such efforts as a global anti-stigma campaign, joining with the Haiti-based nonprofit Partners in Health (cofounded by Jim Yong Kim '82, who is now president of Dartmouth) to inject cancer treatment into health systems already established to treat HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis.

Livestrong's most innovative idea has been its hugely successful corporate fund-raising strategy. Because Nike has sponsored Armstrong since the beginning of his cycling career, Nike was its first, and continues to be the foundation's closest, corporate ally. Nike's Livestrong store offers such items as yellow-and-black shirts, shoes, watches, and hats, all with the Livestrong logo beside the Nike swoosh. Before 2010, the foundation received all the profits from the sale of these items, which amounted to $12 million in 2009. But a new arrangement Ulman negotiated in 2010 encourages Nike to build the brand by splitting the profits. Nike makes a guaranteed minimum annual payment to Livestrong of $7.5 million and then pays a royalty to the foundation on sales above a certain amount. In addition to Nike, Livestrong also has corporate partnerships with RadioShack, Oakley, Nissan, and others. Livestrong is also the first nonprofit organization to brand a sporting park. Kansas City's Livestrong soccer stadium has an enormous yellow wristband glowing at its entrance and the foundation's yellow logo can be seen at every turn.

The Nike arrangement, and others like it, is an example, Ulman says, of "democratizing philanthropy." After all, the money is not really coming from Nike, he says: "The reality is, it's coming from individuals. People are buying the T-shirts." In the past, he says, charitable donations came mainly from the affluent. With the advent of the frequently copied Livestrong bracelet, people of all socioeconomic classes can give a dollar to cancer treatment and raise awareness by wearing the yellow rubber band on their wrist.

What's more, Ulman says, by creating the Livestrong brand, the foundation has created value for the makers and buyers of Livestrong products. Livestrong actually hired a brand valuation firm to figure out the brand's worth, which in turn helps the foundation negotiate the royalties it receives from its corporate partners. This is a far cry from traditional philanthropy, which simply asks people to be generous and give money. By licensing the Livestrong brand to manufacturers, the foundation helps them seem noble and cool, which helps them sell their own products.

Not all corporations are alike, however. Livestrong refused to license its brand to an insurance company, for example. "People are calling the Navigation Center every day, saying, 'I've been denied coverage; they're not paying for my treatment,'" Ulman says. "How could we be taking money from that industry and at the same time fighting that industry? It just didn't feel right."

To Ulman, using a company like Nike vastly broadens the reach of the ninety people working in Austin. To those uncomfortable with the idea of using the fight against cancer to sell products, Ulman says the only question that matters is: "Is this going to help more people with cancer? If the answer is yes, then we do it. If the answer is no, we don't."

Meanwhile, the Ulman Fund continues to grow as well. Although he no longer is involved in day-to-day business, Ulman and his mother sit on the fund's board of directors. The organization now has more than a dozen full-time staff members, including several young adult patient navigators who work at hospitals in the Washington, D.C., area.

And Ulman still sees a dermatologist and oncologist several times a year for a thorough check on his skin. He gets CT scans every few years. The odds of the bone cancer returning at this point are low, but the chances of melanoma recurring, Ulman says, are high.

If he must one day fight cancer a fourth time, Ulman will surely have an awesome, phenomenal, unbelievable team of people to back him.

After all, he's a survivor.

Beth Schwartzapfel is a contributing editor.