Lucia Ewing was in eleventh grade when she staged her "eyeglass rebellion." It was not your average teenage mutiny: no curfew violations, no sex, no drugs. What Ewing did was ask to see an optometrist because squinting at the blackboard was giving her headaches. "You're not getting headaches!" her father shouted. "You're just giving in to prevailing erroneous thought!"

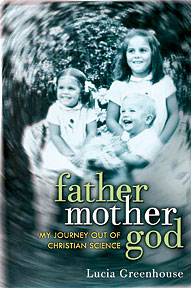

In fathermothergod, her poignant memoir, Ewing (now Greenhouse) recounts what happened when her parents' faith collided with a life-threatening illness. The Ewing family—Lucia is the middle child of three—was, by all appearances, an ordinary Midwestern family. The portrait that emerges over the early chapters of fathermothergod is of kind, loving parents, bicycles and trampolines, camp and school. Lucia's parents converted to Christian Science when she was three, and when she was in fourth grade her father announced that he was leaving his job at an insurance agency to become a Christian Science practitioner. The family moved to London when Lucia was in high school so that her mother could study Christian Science nursing there.

By the time Lucia Ewing arrived at Brown, she had already decided that her parents' faith was not for her. Her visit to health services for her first-ever physical exam caused consternation among the doctors and nurses there. "I had no vaccination history, no medical records," she recalls with a laugh. "I had never been to a doctor, even for strep throat."

But she respected her parents' dedication to Christian Science. In fathermothergod, she recounts a presentation she made in theatre arts professor Barbara Tannenbaum's public speaking course. The assignment was to give a speech to "a hostile audience," and Ewing knew she had her topic when Rhode Island College's fifty-one-year-old president died after refusing medical treatment because of his religious beliefs.

Then one Christmas, while Lucia and her siblings were in their twenties, they came home to find their mother looking ashen and ill. The "little problem she's working out," as their father described it, started the family down a path that would change their lives. Her mother died in 1987.Greenhouse started writing fathermothergod shortly afterwards. Over the next twenty years, she worked on it intermittently as she married, pursued a career in advertising, and had four children.

But it wasn't until her twenty-fifth Brown reunion that she got serious about publishing it. There, she ran into her old friend Kim Witherspoon '84, now a literary agent. "So whatever happened to that memoir you were writing?" Witherspoon asked her. "If you ever finish it, show it to me."

The prose in fathermothergod is refreshingly plain, and Greenhouse's observations are correspondingly clear-eyed and unblinking. While she is clearly baffled by her parents' decisions, you won't find any Christian Science-bashing here. The heart of the matter, for Greenhouse, is: why? Why would two educated people with happy lives (and who had doctors and nurses in their families) choose a religion that rejects modern medicine in favor of prayer? In the end, she arrives at the frustrating but honest conclusion that "parents are ultimately unknowable on some level."

"It'd be nice, in a memoir if you could wrap it all up," she says. "But that would be fake."